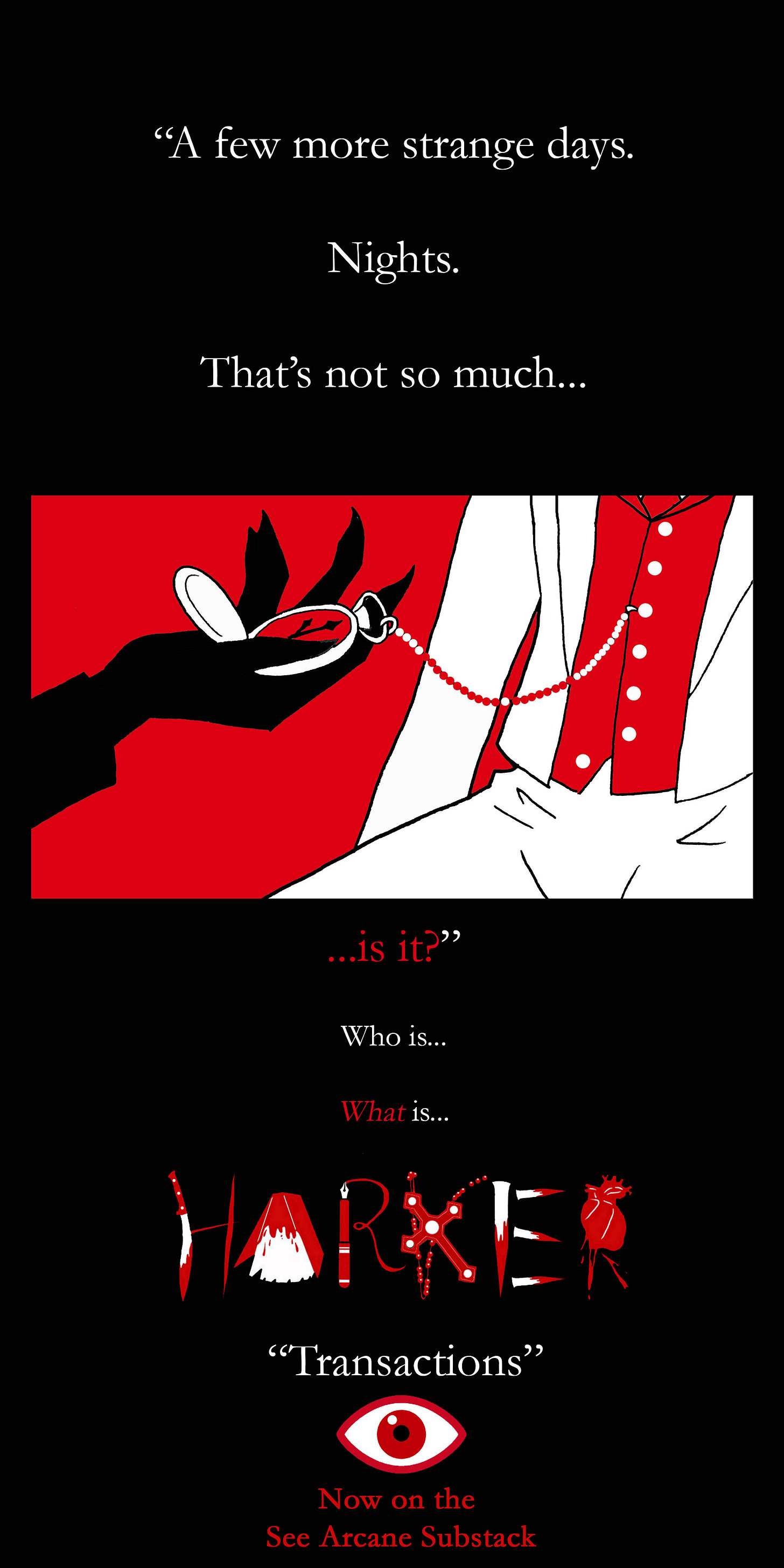

Transactions

Morning was stalled all the way into late afternoon. So late that it was practically the start of evening. Outside the shadows were stretching again, though their spill was a more dramatic view with the castle’s position. The sky slid radiantly from robin’s egg to cobalt, turning at last to pure extravagance when set against the golden outline the sun made of the mountain range.

Back home you get the option of your room’s glimpse of a street or the firm’s view of a brick wall. Even the camera could not preserve this sight in its fullness. When will you ever see this again? When will you afford to come back to these peaks with company?

A vision flitted through him of Mina at this same window, the sun making brass of her eyes as she took in the spectacle that altitude made of the sky. The dream dissolved with a sigh as Jonathan examined his watch. Doing so turned the sigh to a grimace. It was just past five o’ clock. When was the last time he’d slept so late? When was the Count due to return if this was not regarded as afternoon?

“Everything seems pushed back,” Jonathan mused to himself as he dressed. “Trains and time and all. Perhaps afternoon means dusk here. Evening should come around midnight.” Speaking the word aloud spurred memory. Midnight, passed in the frigid dark on the mountainside, wreathed with spectral flames and wolves that vanished with a banishing word. Not a dream, but a thing lived. Jonathan shivered despite his warmth. He saw that someone must have been and gone while he slept, for the logs had been replaced on the fire. Last night’s unease was usurped by equally reflexive embarrassment. Even if it heeded the Count’s own allowance, he winced at thinking of how he must have looked to those strangers; some sluggish guest dozing the day away while they were up and active.

Before stepping out, he retreated to the bed. Partly to marvel with more wakeful eyes at the state of the great structure. Hampton Court could offer no greater majesty in its antique luxury. The damask of the curtains stood richly out from the heavy maroon of the folds, nearly matching the immense spread of covers in their plush design. Habit made Jonathan do his best to smooth and fix the rumpled sheets into the pristine fold he had ruined with his tossing. Unlike the servants’ style, he had turned the sheets down off the pillows. He raised the one he had slept on.

Here was the freshly-flattened wild rose and the journal beside it. Jonathan gathered up the little volume and secured it safe in his pocket. There might be something worth recording in whatever interim was left between now and the Count’s business. His last move was to set the bag dedicated wholly to the Carfax estate by the desk. That done, he passed out into the octagonal chamber and through the dining room door.

The smell of fine coffee met him first. A pot filled with a strong roast was keeping hot over the hearth fire. He spied the array of covered dishes on the table a moment later. His place was set as it had been the night before, this time with the hidden meal being a fine cold breakfast of that sweet sort based in fruit, breads, and plump butcher’s cuts soaked through with honey. A card sat in the center of his gilded plate.

I have to be absent for a while. Do not wait for me.—D.

At least he had not kept his host waiting. He poured himself a cup and ate through as much of breakfast as he could, wishing as he went that he knew the names for half the little dishes.

‘I quite liked this honeyed bread-thing and that bread-thing with the lamb. I especially loved the thing with the berries. Can you part with the recipes to the entire meal? And last night’s supper? Pardon me, let me ask all that again while digging through my dictionary.’

Jonathan huffed at himself. No, he shouldn’t stumble that much. German would be fine enough to limp through. There was even a chance they had some English to spare amongst each other if their employer was any indication. He crossed his fingers and reached for the bell. Or would have, if there was a bell to ring. Jonathan stood and circled the entire grand length of the table searching for one. Nothing. Nor was there any bell to be found around the room. Thinking on it, he couldn’t recall the Count having rung one last night when supper ended. The staff must operate on some private rule of action once a room was left empty.

No, that can’t be right. They refreshed your fire while you were sleeping. It must be a rule of acting while unobserved. Supposing it really is a rule and you are not just inventing reasons to be skittish.

For Jonathan inched closer to unease as he dwelled on it. A castle’s worth of servants all dutybound not to be observed, to act only when a back was turned or eyes were shut. Meaning they would have to be aware of him without his knowing. Right now.

“Hello?” The word made no impression on the air. He tried it in three different tongues, hello, hello, hello. He might have welcomed the awkwardness of someone poking their head in and catching him, if only to see that someone face to face. But no one came. It did little to erase the conviction that he was observed. The feeling came with him to the eight-sided room where, the moment he closed the door behind him, he laid his ear to the crack. All he heard was the crackling of the hearth. No echo of footsteps. No shuffling of plates and cutlery. Nothing. As if to punish him for his would-be eavesdropping, there was a cry of wolves in the distance. “It cannot be late already,” he insisted to the quiet of the room.

It was rather difficult to call the octagonal space only a room, considering its proportions. It might have cradled a little house between its eight walls. Jonathan followed them around by foot and by eye. It had already been lit when he’d left his bedroom and was still aglow now. Ponderous doors sat in each wall, suggesting a dizzying layout no matter what lay behind each. How would the halls lay against each other? How were the rooms not wedges? The architects must have been predecessors of the modern illusionist, making magic of geometry. At least enough to slot stone and timber together in a way that maximized space in all directions. Jonathan lauded them even as he sighed over the choice of furnishings.

Namely, that none of the furnishings held much in the way of distracting material. There was Dantès still waiting in his luggage, but curiosity insisted he give at least one good try for local literature, or even a newspaper. At least as far as he might try within the space the Count guided him through; he didn’t yet dare to go prying around the building without the man’s say-so. Nor was the timing right to don his rougher shoes and go tromping around outdoors to have a true look at the castle. He’d wasted too much of the day for that.

So he made his circuit of the eight walls, regarding paintings and tapestries and doors with equal wonder. The first of the latter he tried was the one directly opposite the bedroom. Locked. The next bore fruit enough to banish all but elation from his head.

Here was a library to make those in London seem threadbare. Shelves swallowed every spare inch of the walls, the size of which staggered in their height. It was apparent that Count Dracula had no intention of being an unprepared citizen of England, for there was a mountain range in miniature dominating the low table set before the couches and chairs, all to do with the facets of English living. Here were books on customs and fashion of the day, on history and present politics, on geography and botany, all littered through with guides and magazines and newspapers and journals of every subject as it pertained to the country.

One bookshelf carried a contemporary row of updated informational texts. Jonathan’s eyes skimmed directly over an almanac and directory to recognize the Law List. His hand went to it and might have drawn the volume out for familiarity’s sake—it was, he noted, a newer printing than his own at home—but his eye caught on the shelf above it. And from there the shelves above that. It appeared that the entire wall was populated with English reading material. Not merely of the educative or English-born fictions, but translations too.

Specifically, translations of works that populated the room in their original languages. Novels and histories and textbooks of all kinds that had their first printings across multiple countries were present, even volumes that had been bound for the first time in centuries past. Jonathan felt his heart stop entirely when his eye landed on a curio whose tall glass doors showed what looked like a 15th century manuscript of The Divine Comedy perched above a shelf dedicated to early bound editions of The Hermetica, their spines sporting titles of Egyptian, Arabic, and Grecian text. Below that was a copy of the script for Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus on a folding stand beside a leatherbound copy of, ‘The English Faust Book,’ still flaunting its full ramble of a title, The History of the damnable life, and deserved death of Doctor John Faustus. A carved mask of Comedy stood between the two volumes.

From here Jonathan traced his way around the entire library as though exploring a museum. He feared to touch half the volumes that were on the open shelves, dreading the idea of accidentally prying open a treasure printed a hundred or more years ago and fumbling it. Still, he thrilled at recognizing an older title and pacing back to the wall with its English inventory to discover that the Count had bought its counterpart.

Jonathan thought bittersweetly to the far end of childhood, back when both parents had started to lay down text in his grandparents’ tongues so that he might translate all alongside English. They had only managed a few scraps before the end. His aunt had little enough to offer after he was under hers and her husband’s roof, and her husband had swept the notion away entirely. What use was the Gurkha talk and Persian twaddle when there was the country’s proper language to learn? If the boy must take in another tongue, let him swallow some Latin.

The storm cloud forming over his mood dissipated again when he came upon, of all things, a section dedicated to folk legends and myths native to various lands. Tucked beside a weighty volume dedicated to King Arthur and his knights was a collection that made up the entirety of Arabian Nights. One set in the original Arabic, the other in English. He had been just brushing adolescence when he first sat down to read an edition of the latter; abridged and edited, he knew, but far heavier than the few stories his mother had picked out for him to practice by. His face had flamed upon reading why.

For every story that had engaged by its adventures or hidden education, another nettled with its cruelty or warped lens of love. It was no surprise to him as to why the collection was foundational literature, but its framing still curdled something in Jonathan’s chest.

Scheherazade, Scheherazade. You and Bluebeard’s widow ought to have met.

He was still dwelling when he heard the door swing open.

“Good evening,” the Count said as he let the door fall shut. “Did you have a good night’s rest? Pardon, a good day’s.”

“I did. Though I wish I had not drowsed the whole day away.”

“My people and I make a joke of what the clock tells us. If we must sleep, we sleep, if there is work, we work. Such is the way of life when our world is perched here, away from the city schedules so far below. And see? The sun is down and here you are busy with the books.” Jonathan watched with a strange relief as the Count’s expression softened. One broad white hand trailed along the nearest volumes with open fondness. “I am glad you found your way in here, for I am sure there is much that will interest you. These companions have been good friends to me, and for some years past, ever since I had the idea of going to London. They have given me many, many hours of pleasure. Through them I have come to know your great England; and to know her is to love her. I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is.” He feigned a less than hearty laugh and threw up his hands. “But alas! As yet I only know your tongue through books. To you, my friend, I look that I know it to speak.”

Jonathan started at that.

“But Count, you know and speak English thoroughly.”

The Count bent himself in a half-bow even as he shook his head.

“I thank you, my friend, for your all too-flattering estimate, yet I fear that I am but a little way on the road I would travel. True, I know the grammar and the words, but yet I know not how to speak them.”

“Indeed? You speak excellently.” It was the truth. Even with his inflection, there was an elegant precision in the old man’s speech. Jonathan had come to recognize the phenomenon as it exerted itself on those learning more than their mother tongue. The student learned the language to its exact notes of syntax and so came out sounding more pristine in their speech than one who had grown up with the language and so turned the words to slang and slush. The Count appeared almost to read this thought as it came to him and grinned.

“Not so. Well, I know that, did I move and speak in your London, none there are who would not know me for a stranger. That is not enough for me. Here I am noble; I am boyar; the common people know me, and I am master. But a stranger in a strange land, he is no one; men know him not—and to know not is to care not for.”

Jonathan caught his tongue before it could fly and dare an interruption. Yet he still thought as loud as he could:

Experience says otherwise, Count. So does the sign of the Son resting under my shirt.

“I am content if I am like the rest,” the Count hummed on, “so that no man stops if he see me, or pause in his speaking if he hear my words, ‘Ha, ha! a stranger!’ I have been so long master that I would be master still—or at least that none other should be master of me.” In talking, the Count had strolled until he might have walked directly into Jonathan. Jonathan in turn retreated some steps toward the waiting couches and chairs. He might have backed entirely over a chaise had the Count’s hand not grasped his shoulder. This time he had braced for it and so managed not to shudder. The Count beamed down at him. “You come to me not alone as agent of my friend Peter Hawkins, of Exeter, to tell me all about my new estate in London. You shall, I trust, rest here with me awhile, so that by our talking I may learn the English intonation; and I would that you tell me when I make error, even of the smallest, in my speaking.” The Count’s face shifted into an apologetic moue. The cold hand squeezed. “I am sorry that I had to be away so long to-day; but you will, I know, forgive one who has so many important affairs in hand.”

“Of course,” Jonathan heard himself say in a too-thin voice. He swallowed and tried again, wishing the chaise was between them, “I cannot vouch for myself as a model teacher, but I shall do what I can. I must warn you, though, that my tone is not that of a Londoner, and quite far removed from someone of your status.”

“Ah-ah, you give yourself away. That you know the difference of a voice between cities and classes means you have harkened to both.” Another grin flashed. “Is it not so?”

“I suppose, sir. I only wished to give you fair warning. You may still want to hire a formal instructor once you reach England.”

“A concern to save for England,” the Count assured. His hand moved from the trapped shoulder with a parting clap that almost toppled Jonathan over. “But I have you here and now, and so I shall reap what I can.”

“Might I do the same? That is,” Jonathan was staggered again as he took in the sheer scale of the room, “may I visit this room throughout my stay?”

“Yes, certainly,” the Count nodded. “You may go anywhere you wish in the castle, except where the doors are locked, where of course you will not wish to go.” His eyes found Jonathan’s again. Even without firelight to blame, they had a distinct scarlet gleam to them. A medical mystery, Jonathan thought, like the oddity of the man’s hands. The gaze seemed to flare despite the mild light of the room’s lamps. “There is reason that all things are as they are, and did you see with my eyes and know with my knowledge, you would perhaps better understand.”

“I do not doubt it.” Jonathan dug up a smile. “All houses have their rules and reasons for them.”

“So they do. But I fear you think only in terms of English houses.” The Count’s smile now bared his teeth all the way to the gums. “We are in Transylvania; and Transylvania is not England. Our ways are not your ways, and there shall be to you many strange things. Nay, from what you have told me of your experiences already, you know something of what strange things there may be.”

“I know only enough to understand that I know nothing, sir. In truth, I had hoped to ask you for some illumination on a number of matters that have been hinted to me rather than said outright as I traveled to the Pass.” The Count clicked his tongue at this and circled around to one of the tufted chairs. He took a seat as he motioned Jonathan to take another.

“Such is so often the way with the peasants when handling a stranger. I take them as my example of what there might be to fear in England. You must know the land already, for you will never learn a thing from the native people. Tell me what things have troubled you, my friend, and I shall explain what I can.”

So began a conversation that fattened the minutes into well over an hour.

It was a talk that felt to Jonathan like a mutual game of discretion more than an open discussion. Jonathan spoke as much as he could upon the subjects that had so confused and worried him, but, even in the face of the Count’s inquiry as to actual persons involved—

“What people were these at the Golden Krone who so disturbed you, my friend? Can you recall them or the fretting companions of the coach?”

—or what tokens they had gifted him in their earnest fear, he laid more weight than was true upon his inability to piece any identifying features together. He was himself a stranger and so everyone seemed at once alien and alike to him. The landlady’s crucifix laid especially warm against him as he insisted it was only a handful of passing guests who had hinted at evil spirits holding sway on his journey.

“I wish I could say I took it in stride as I am sure they intended me to, but they were all too candid in their performance for me not to take a little of genuine fear along for my ride. I only wish I could have gleaned from them the actual stories and devils they hinted at without telling the whole. The most straightforward word I received on the matter I had to eavesdrop for.”

Here Jonathan described the terms overheard on the coach. The Count nodded at them all, his eyes seeming to flicker with their own flames over specific words. Some he even laughed at. When Jonathan asked why, the Count merely waved his hand.

“It is nothing, my friend. Only, it amazes me how far their imaginations have strayed. As though the monsters they have invented and the legends they crawled from ever obeyed a calendar fashioned by men. Do you think the supposed evil spirits of Hell were waiting patiently beneath the Earth for Saint George to live and die and make a special occasion of your harrowing night? No! Such things, should they be real, would be as old as the mountains! Older! And still the ignorant will fret and shiver over a night they decide is haunted or holy by turns. Likewise for the wickedness and revelry of Walpurgisnacht and for all holy and unholy days. At best, some peoples long ago noticed something bizarre or unexplained around a certain time of year and told themselves, ‘Yes! Yes! A god did something this day! Or a saint or an abbess or a witch or a demon! How do I know? Well, this strange thing occurs at this time, so it must have something to do with some special character of my own faith!’ And on and on it goes around the world.”

“Then the talk I heard—,”

“All nonsense,” the Count cut off. “Some of which I will confess bewilders me. Talk of witches and wolves, this I recall from stories told to me by my elders. But vampires? Satan himself?” The white face twisted with a look of comic confusion. “They have begun fattening up their nights with more horrors to swoon over like children babbling ghost stories. Next year they shall have twice as many devils to shriek over. This, when, if such things were so terribly rampant, the people would have left for less haunted ground long ago.” Saying this, the Count leaned as if to impart a secret. “They frighten themselves, you see. It is something to do to pass the time and keep their young in line. Better, it is something to make them feel brave even as they live in a land of beauty, peace and protection far from the hectic norm of the wider world. They need fear no man in our terrain and so they dream up monsters in their place.”

“You make a fair point, sir, but that leaves me at a loss for what I have seen firsthand.” Jonathan bit his tongue too late. The Count’s eyes shined above a new grin. “That is, what I may have seen. It could have been a thing I dreamt in the ride up here.”

“Do not be so quick to doubt yourself. An absence of monsters is not an absence of all things fantastical.” Jonathan watched the Count’s hands weave into each other. The pointed nails seemed longer. “Tell me, what did you see?”

“I believe I saw blue flames in the forest the other night. Small fires that hovered just above the ground like will-o’-the-wisps. The coachman stopped to mark their places with a mound of stones as we headed up to the castle. Once I thought I saw their light burning through him. Hence why I suspect I am mistaken in the memory. The coachman himself would be better to ask.”

“There is no need,” the Count half-laughed. “I know what you speak of and what the coachman sought to do. You saw those blue flames as surely as he did. Last night, be it Saint George’s or not, was a time worth acknowledging. Evil spirits holding sway, yes, but more practically, a time of visibility. Those blue flames are said to appear directly over a place of buried treasure. Dead men’s gold. That treasure has been hidden in the region through which you came last night. There can be but little doubt for it was the ground fought over for centuries by the Wallachian, the Saxon, and the Turk. Why, there is hardly a foot of soil in all this region that has not been enriched by the blood of men, patriots or invaders. In old days there were stirring times, when the Austrian and the Hungarian came up in hordes, and the patriots went out to meet them—men and women, the aged and the children too—and waited their coming on the rocks above the passes, that they might sweep destruction on them with their artificial avalanches. When the invader was triumphant, he found but little, for whatever there was had been sheltered in the friendly soil.”

There was unmistakable pride in the words. They actively straightened the Count into his full height and turned the flaming gaze to some unknown distance, as though he could see the country’s ancestors still perched along the mountainside to cheer as their rockslides crushed the enemy, or the cursing invaders as they found all the riches hidden. Though this still left a question unanswered.

“But how can it have remained so long undiscovered, when there is a sure index to it if men will but take the trouble to look?” Jonathan watched the fondness harden to a sharper glee. He leaned away from it by some inches.

“Because your peasant is at heart a coward and a fool! Those flames only appear on one night; and on that night no man of this land will, if he can help it, stir without his doors. And, dear sir, even if he did, he would not know what to do. Why, even the peasant that you tell me of who marked the place of the flame would not know where to look in daylight even for his own work.” The Count regarded Jonathan coolly. It felt not unlike having a gun leveled between his eyes. “Even you would not, I dare be sworn, be able to find these places again?”

“There you are right,” Jonathan answered. “I know no more than the dead where even to look for them.” He was fairly sure he spoke the truth. Just as he was fairly sure he would rather not bring up the coachman’s trick with the wolves. In fact, he was fairly sure that it would be better for him to scrape the entirety of the eve of St. George’s Day out of the conversation. And so, “If I may ask, is there any reading you would suggest that expands on the legendry of the Carpathians? I found little on the subject back home, but perhaps if I knew what author or title to trust I would have more luck.”

The Count raised one snowy brow as he asked, “Why was it you were looking into the lore of the land, my friend?”

“Because I remain a victim of my classroom customs,” he answered. The Count made a new face at that. One less like an aimed rifle and more like one who had expected an animal to howl, only to hear it sing a melody.

“How is that?”

“I set out to study a single subject—that is, the general background of the Carpathians—and before I knew it, I started chasing every offshoot of knowledge connected to the subject, however thinly.”

“Such as..?” Jonathan found himself detailing the whole of his spree in London’s libraries and museum offerings, all the history and heritage he had been able to dig up over the days of preparation for the transaction. The more he went on, the warmer the Count’s mien grew. He seemed nearly to glow when Jonathan mentioned that, however false or true, he had assigned himself the task of collecting what he could of local legends and phantoms to bring back home. “To your fiancée?”

“Yes. We are both avid amateur archivists, given the right excuse.” Jonathan caught himself with an easier smile as he sighed, “I could see her as an author before the decade is out.”

“Why not yourself?” The Count canted his head at him. “It is you hunting for spirits here, hoping to preserve them.”

“And I think I can do so. I can even tell myself that my rambling prose will come near to describing things with the gravity they’re owed. But even if I were to be as verbose as Dickens, I doubt I shall ever think my translation of sight or story is equal to the thing itself. I know for a fact that I could wring a dictionary dry of every adjective and never measure up to describing what I have seen of this land so far. I would waste whole pages in depicting the warmth of the towns, the endless emerald spread of the forest, the way sunset paints the mountains; a paltry description on paper and, to most ears, I think, far too saccharine to hear.”

“What is sincere is not saccharine,” the Count chided. “You are fresh from the world beyond Transylvania and so come with new eyes. The people here, they take all of their home’s luster for granted. You would do it justice, I am sure, if you were to stay and make a written portrait of it.”

“I would welcome the chance. But time and duty take priority, and so I will record in miniature for now. What is it?” Jonathan saw the Count stifle a laugh with one hand and wave off his query with the other.

“Forgive me. It merely amuses me that we sit here pining for the other’s homeland. I crave your cities, you sigh for my mountains. If it were not for the great turning wheels of property law and paperwork, we could settle the matter by a mere trading of house keys. On the topic, let us cease our stalling of business.” Count Dracula folded his hands again, this time to make a rest for his chin. “Come, tell me of London and of the house which you have procured for me.”

“Of course,” Jonathan said, already out of his chair. “My apologies, sir, I ought to have laid things out last night.”

“If you had, we would have fallen asleep where we sat. I am no boor who would crack his whip at servant or guest to rush simply for the sake of rushing. We have plenty of time and wakefulness to us now. Go, gather what is needed, but do not sprint. More, as client and master of the house, I order you even to dawdle.” The Count made a shooing motion after Jonathan as he made his way through the door.

Through the octagonal room, into his bedroom, up to the bag at his desk, all was quiet. But the moment he began to place the documents in order, there was a sudden brisk rattling. A noise of plate and glass and cutlery. It ended in seconds. When Jonathan passed back into the eight-sided chamber, he saw through the dining room’s door that it was aglow with lamp and hearth. His eyes stuck to the table—finally cleared.

In a single moment too. Were they waiting for me to be further off? It cannot be the Count’s presence that prodded them into action. He had to have noticed the table before reaching the library. So why?

Jonathan could think of no answer by the time he returned to the library. It was thankfully far brighter than when he’d left it. All the lamps were lit rather than a mere half. Night had piled itself against the windows and turned the air glum as he and the Count spoke. Now it was as welcoming as he’d found it when he first came to ogle the shelves. The Count himself was taking advantage by way of reading on the sofa. It was a tickling sight, for his host had chosen an English Bradshaw’s Guide to thumb through. Amusement tipped briefly toward homesickness—

You see, Mina? My client has only the best of reading material in his collection.

—before he locked himself firmly into the role required of the transaction. The Count matched him in an instant, rising and clearing the clutter from the low table so Jonathan might lay out the full paraphernalia of the estate. The next few hours transported Jonathan back into the pre-examination haze, answering a litany of questions about every possible detail of the grounds and the necessities of the sale. Said inquiries being loaded with facts already gathered ahead of the exchange.

“Carfax Abbey,” he smiled over Jonathan’s offered photographs. “It is just as I had hoped. A gem of ancient craftsmanship, built facing all directions unobstructed. No doubt it was once a place of strategy more than holy service at its inception. The people respect it still, if only in building so far from its borders. An asylum is the closest of all, yes? The house of madmen that stands as less than a speck on its horizon. Apart from this, the estate is private in its acres?”

“That it is,” Jonathan agreed with no little admiration. “You seem to know the whole of the place as well or better than myself, Count.”

“Well, but, my friend, is it not needful that I should? When I go there, I shall be all alone, and my friend Harker Jonathan,” the Count held a hand to his breast with another nodding bow. “Nay, pardon me, I fall into my country’s habit of putting your patronymic first. My friend Jonathan Harker will not be by my side to correct and aid me. He will be in Exeter, miles away, probably working at papers of the law with my other friend, Peter Hawkins. So!”

He knew how to say Peter Hawkins’ name an hour ago.

Jonathan could not place the thought’s voice in time—Mina’s protective pitch? His own whisper taking private tally?—before the Count plunged them on through the purchase. Details were noted and copied out, signatures were scrawled in the Count’s marvelous old script before the old man produced stationery for Jonathan himself, sitting by and splitting his attention between watching how Jonathan wrote out the confirmation letter and flipping again through the small album of Carfax’s photographs. He waited just until Jonathan had sealed the envelope before laying the pictures down with a question.

“How did you find such a place? I have so long read of dear London’s modernity that I feared my hopes, my requests even as a client, were doomed to disappointment. In truth…” Here he leaned again as if to impart a grave gossip’s secret. “I was forced to learn an unpleasant lesson from other, less thorough parties than yours and good Peter Hawkins. They took my desires in an estate as mere suggestion, even a joke. I was provided only images of fresh-faced manors and contemporary constructions with the scantest connection to what I had asked.” A thunderhead came and went in the Count’s expression before breaking on a truer smile. He brandished one of the photos at Jonathan like a pointing finger. “But then here you are, bringing me a home crafted from my own wishes. How was it that you uncovered such a place?”

“Oh,” Jonathan opened another folder and slipped out his typewritten notes, “I actually have the day recorded here.”

Here he went over the vision from the by-road, the ancient build of the estate, his theory of Carfax being born of Quatre Face, and sundry other findings of the acreage it encompassed. All the while Count Dracula settled happily back into the cushions as if he were sinking into the sound of a fine song. Jonathan found himself grateful, for the Count had made him sit parallel on the couch as they went through the documents. It had been all he could do not to mistakenly brush him or grow entangled in his host’s reaching arm as they went through the papers. Now, with hands folded at his lap and eyes shut, Jonathan wondered if his host might have fallen asleep.

Does he look asleep? Or does he look…

Dread trembled through Jonathan for one awful heartbeat. For that moment he feared the cadaverous pallor, the stillness of the old man’s chest, of his whole person. It was a moment that tolled just as he had finished his recitation and left a swelling quiet after it. Jonathan neither saw nor heard the Count’s breathing. Alarm grew with the silence.

“Sir?” The Count was still. “Count?” Still. A memory of old horror turned over in him—

Sleeping sleeping they’re only sleeping please please please sleeping

—before Jonathan closed the gap between them on the couch. He set his hand lightly on the Count’s arm. His wrist. Cold, of course, always cold. But the pulse. Where was his pulse—?

Jonathan blinked. His hand was locked inside the Count’s.

“I…” Jonathan choked, digging frantically for words as the Count regarded him with eyes only a slit open. “Forgive me, sir, I did not mean to—to overstep, or—,”

“Calm yourself. You only worry for an old man who has far outlived what years were expected of him.” The white hand tightened. Not enough to crush, but enough to all but weld their hands together. Jonathan could feel the strange down in the Count’s palm grate against his skin. “My thanks for your concern.” The swipe of the old man’s thumb over his knuckles. “Between this and the house, you have brought me more than I have yet dared to expect from another in ages. To that end,” the Count released Jonathan’s hand to grab up another of Carfax’s photographs, “I am glad that it is old and big. I myself am of an old family, and to live in a new house would kill me.”

The Count did not shift from where he lay in the cushions, nor did his eyes move from Jonathan’s. In turn, Jonathan did not quite dare to move back to his place at the couch’s other end, instead sat frozen and listening as the Count spoke of habitation, of old chapels, and the Transylvanian nobles’ joint wish not to lay with the commoner in death. He mused on avoiding youth’s gaiety, for he was an elderly thing and full of mourning for the long-dead, craving cold shadows to dwell alone in. All this and more he recited as if from a held script. Jonathan might have believed every word if he had been able to close his eyes.

Yet his eyes were open and so could not miss the contrast of the Count’s face to his speech. It was a look that carried something dark inside, like a poison hidden in honey. Again, Jonathan found himself tallying:

‘I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is.’ His own words. Can he mean it all? Or is it by half alone?

“Ah, is that already the hour?” He fell back into himself as the Count turned his attention to his watch. Not the Count’s own. Jonathan saw he now sat less than an inch from his host, whose hand had filched the watch from Jonathan’s own pocket. He bristled as the Count set it back in its place. “You let me go on too long, Jonathan. My people here know better than to allow my tongue to fly, eating up the time. Please, I ask that you put all papers and those in need of posting in order; I trust your judgment more than my own in this. Meanwhile, I must see to some private matters of my own.”

Jonathan heard himself speak an affirmative as the Count swept out of the library like a breeze and closed the door after him. He could not bring himself to move until the chill carried by the watch had thawed away. With one ear tilted toward the door, Jonathan arranged the paperwork with only the power of habit steering him through. Once all was in order, he jerked himself up and over to the bookshelves again. Something. He must be preoccupied with something.

Why not the journal?

Because.

Because?

Because if he catches you putting it away, the Count will know there is something else to borrow from you. And where to find it.

Jonathan stopped his hand short of tracing the journal’s outline by throwing it at a random volume. It turned out to be an atlas. One published the year prior. He slipped it out and found the book opened instantly to England’s map. The pages had been pinned by frequent use with the country itself pocked with three circles inked along its eastern side. One near London—

Carfax Abbey. Mr. Hawkins must have sent a map along with the rest of the correspondence.

—one around Whitby—

It really will be a crowded summer by the sea, Mina. Visitors are coming all the way from Transylvania to enjoy the view.

—and one around Exeter.

The smile Jonathan had been struggling with fell apart. He held the atlas closer to the nearest lamp, but there was no mistake in the light. Exeter. Beside the black circle was a small point in red ink. Looking close, he saw the same mark repeated near London, floating almost at the edge of Cambridge. Only this one had an X drawn through it. Deep enough that the paper had almost been pierced through.

Hawkins and I must be the Exeter mark. Did he try another firm first?

Tried and was disappointed. A little chill ran through him as he touched the dented X in the map.

Stop. You must stop. If not you will catch yourself jumping at everything within the week.

The thought was cut short by another voice. Not his own.

Jonathan, Mina rang in his head like a sweet bell. Do not lose your sense to self-doubt. Do not smother the warnings you give yourself with irrational rationality.

Doubt of what? Warnings for what? He was unmoored, unnerved, unsettled, all true, but it was foolish to be so to such extremes. If the Count was overfamiliar, then it made him only one of many who had helped themselves to his person, albeit out of fear and charity. Jonathan was the foreigner in an unknown land and could not know all that was natural to the place and its people.

Very true. And what do you make of the place and its people? What of Count Dracula’s own standing among them?

‘At odds,’ would be the politest way to put it. There was no softening reality when he thought of the Golden Krone and the coach’s horror at learning his destination. No more than he could deny that the Count held the ghosts of citizens dead for centuries in higher esteem than his living people of the present.

Again, true. But I do not speak of Transylvania. What of the people here, Jonathan? In the castle. Why have you seen none? Heard none? True, the structure is vast, and perhaps they are under orders not to be seen by you. But if so, why? And if not…

If not?

Think of the people below. All afraid. Just the mention of the castle sealed lips or set off tears. The whole coach screamed at the sight of the man come to take you to the Count. They did not fear St. George’s Eve an ounce as much as they feared that driver. Who among those people, among their unanimously terrified kin and friends, would dare to live here?

Jonathan thought of the driver. A tall man muffled in gloves and beard and masking hat. The strength of him, the unanswered mystery of his control over the wolves. His eyes shining red as embers.

At best, a relative. But would the Count call his own kin a peasant? Where is that coachman now? Why is it that in halls where every footfall echoes like a stone tumbling in a cave, yours and the Count’s are the only steps you’ve heard?

Steps he could hear now. The heavy fall of the Count’s boots. Jonathan slid the atlas back in its place and snatched out the Law List just as the door opened.

“Aha! Still at your books?” His host closed the space between them with a quick stride. As soon as he was in reach, he plucked the book from Jonathan’s hands with a musing look. Its pages had a natural way of opening as well, this time on a section to do with the handling of multiple properties. Jonathan watched him clap the volume shut and replace it without turning his head to face the shelf. “Good! But you must not work always. Come, I am informed that your supper is ready.”

Jonathan found his arm abruptly hooked by the Count’s. He was towed more than led out of the library and back to the dining room. Again, only his place at the table was set, again the meal was of stunning quality, again the Count himself pulled away the covers of every dish, and again the Count pardoned himself from dining as he had taken his meal early. Jonathan carried on conversation as best he could between bites. His only complaint, very much unvoiced, was a wish that he might have water in place of the new helping of wine, fine though it was. He took only shallow sips, thinking he might make it out of the meal with the glass still half full.

“Would a claret be more to your liking?”

“Pardon?”

He looked up from his plate to see the Count watching him. As he did, his host’s line of sight flicked to the glass.

“You do not seem as fond of the Tokay this time. Is it because you prefer another type? Perhaps something stronger?”

“No, the Tokay is wonderful. I only wish to avoid speaking senselessly, as I fear I did the other night.”

The Count laughed, “If that was you at your most senseless, then sobriety must leave you mute. Come, I insist you finish your glass, if only to save it from being wasted. I am unable to indulge—indeed, my health is such that I can consume only the strictest portions—and so I would enjoy what I did of old through my friends.” With one hand the Count pulled the emptied plate away from Jonathan while the other set the waiting wineglass in its place. “If for nothing else, I ask that you toast on my behalf. To the making of a new home.”

“To your home, then,” Jonathan smiled over the raised glass. “May it bring you every joy and comfort.” He got the crystal to his lips for only a moment and a single taste within it. Then he was drowning. Or would be, had he not quickly tipped his head as the Count took hold of the glass over his own hand, raising it up so that he had to quaff rather than savor. Once the glass was empty and he was free to breathe and cough, the Count struck his other palm against his back.

“Save temperance for another day, my friend. You will finish the bottle and more before we part ways. Just as I hope you shall make a fair dent in the cigars.” This sufficed for invitation as the Count again took Jonathan’s arm and ushered him to their place beside the fire. A cigar was pried from its brothers and lit by skimming it through the flames of the hearth. Jonathan took it with a practiced smile, his puffing feeling somehow like a chore more than a pleasure. But an easy chore, at least. As was the conversation which unfolded over hours through the night. Not least because Jonathan found himself pinned under an avalanche of fresh inquiries.

These started off in the expected way, being littered with questions as to the state of England according to an Englishman. Everything from the latest in politics to plays, trains to telegraphing. Jonathan was in the middle of lauding the distractions of Piccadilly Square when a peculiar chill crawled along his spine.

Dawn is turning over now, he thought. The hour when the dying most often turn over to death. You heard that for the first time at the funeral, didn’t you?

“Careful,” a different chill brushed Jonathan’s fingertips. The Count tweezed the glowing nub of the cigar from his hand. “You risk burning yourself as your mind wanders. Is Piccadilly so grand a destination?”

“It has the advantage over most of London’s offerings in my memory, sir. I am no frequent visitor, but Piccadilly has the honour of being the backdrop for some of my happier outings with,” Mina’s smile flashed up in his mind, “friends in the past.” Outside a cock began to crow. It was a piercing sound that might have reached all across the mountain range.

Is that truly how quiet it is up here without your voice or the Count’s to break it?

“Why, there is the morning again!” Within a blink the Count was up out of his chair. “How remiss I am to let you stay up so long.” This time Jonathan was ready as one of the cold hands found his shoulder, squeezing it in farewell. “You must make your conversation regarding my dear new country of England less interesting, so that I may not forget how time flies by us.”

Count Dracula gave him a parting bow before briskly taking his leave. Jonathan had scarcely gotten up by the time the door closed. He remained there with the pocket watch in his hand, ticking off a quarter of an hour. Out in the octagonal room, Jonathan waited for the same period with his ear to the door. He repeated the wait again inside his bedroom. Listening, listening. Nothing.

But there was at least one sign of others coming and going in the room itself. His bed had been remade in the original folded style and the curtains were drawn over the window. He pulled them open just enough to peer out at the courtyard and the cotton-grey of sunrise thawing away the night’s black. As he was about to pull the curtains shut again, his eye caught on the windowsill.

The mountain ash he had wedged in the stones was gone. He discovered the same of the wild rose he’d left under his pillow.

“Cleanliness outweighs superstition, I suppose.”

Though he wished the staff might have asked him first. To that end, they must have known what the plants were for. At least better than he himself knew. Whatever their purpose, they had been given in earnest so that they might bring good luck in some way. His left hand floated up to the crucifix still resting under his shirt. He continued to rest his fingers there as he took the journal out and wrote his record of the night:

7 May.—It is again early morning, but I have rested and enjoyed the last twenty-four hours. I slept till late in the day, and awoke of my own accord…

It is only a little embellishment. There was more that was pleasant than not, wasn’t there? And the sale! It’s done! All over but the posting and then all is complete. Give or take a few more days. A week’s length at most if the Count is intent on our midnight talks.

His pen paused.

You shall, I trust, rest here with me awhile, so that by our talking I may learn the English intonation…

The Count had spoken of reaping what he could while Jonathan was with him, that he would worry over the exactness of a noble’s speech once in England. But it still rang as odd to him. Exeter was not London and he was only recently graduated from the role of a solicitor’s clerk; one who had barely inched into his second decade of life. Would the man truly be satisfied speaking with the accent of a boy from Devon?

He might if he was lonely.

The pen sweated out a black drop that broke into a stain at the page’s corner. Jonathan set the pen aside as he waited for the spot to dry. Thinking as he did.

Thinking of whole towns that regarded an old man and the mere sight of one of his people as a nightmare worth screaming at. Thinking of a broken old castle that was so vast that its staff were invisible as ghosts, forever unseen and unheard. Thinking of an old man, a noble, who answered the door and took the luggage with his own hands, who held up a threadbare excuse of lessons in language as reason enough to draw out a guest’s stay even after their business was concluded. Thinking of that old man, doubtlessly hovering at the edge of Death’s threshold, using the last of his time to settle in a house in reach of London’s thrumming city streets, where no one knew him, where even with his ample acreage there would be the nearness of people.

Thinking of how the old man’s hands had settled on him over and over again.

Lastly thinking, almost absurdly, of the people who knew him at the Aerated Bread Company. Most were women. Some young, some old, some married, some not, some widowed. They would talk over lunch, indoors or out, and the eldest of them, weathered by loss and age, would inevitably touch his hand or cup his shoulder or, even as the restaurant’s people feigned being aghast, press some tin or other into his hands, full of things preserved or baked at home, really, young man, you will waste away otherwise! And in turn, when he returned the tin with something he had made, eyes would dew and smiles would crinkle even as they chided him for spoiling their appetite before they had even touched the menu, for shame, but it is lovely just the same. Grasping his hand, his shoulder, thank you, young man.

‘I thank you, my friend, for your all too-flattering estimate…’

My friend, my friend, my friend.

The page was dry. His pen scratched on.

A week. Two at most. And Mr. Hawkins wouldn’t want me stepping on a client’s goodwill, especially after a purchase. Just a little while longer. That’s all.

“A few more strange days. Nights. That’s not so much, is it?” The walls did not answer. Unease still turned in him. His hand traced the crucifix again as he took himself and the journal to bed. “The trouble is being inside all this time,” he decided. “You will wake before sundown today. Go outdoors and really see the place.” Jonathan resolved to follow orders. It would be easy enough, for there was very little fatigue behind his eyes. He slipped into a drowse as the rooster cried again and again.

Aaah it is thick with atmosphere. The repeated emphasis on fear, whispers, and the isolated setting of the castle creates a palpable sense of unease and dread. The question "If not...?" is a stroke of understated horror.

Jonathan is portrayed as intelligent but also naive and vulnerable. The internal debate about self-doubt and "irrational rationality" is compelling and creates a sense of realism.

Also, the central mystery surrounding Count Dracula and his castle is well implemented despite the modern reader knowing the answer (unlike the 1890s one). Questions about the absence of servants, the fear of the locals, and the strange behavior of the coachman... The hints about the Count's peculiar habits (consuming only "strictest portions," his unhealthy pallor), his overfamiliarity, and the intense fear he inspires effectively foreshadow dark secrets. The references to dawn, death, and the funeral create a sense of impending doom.

The shift from general inquiries about England to the chilling observation about dawn is seamless and unsettling.

The internal monologue is distinct and believable, adding depth to Jonathan's character. The Count's formal and subtly menacing dialogue highlights his power and control.

Jonathan's internal struggle between dismissing his fears as irrational and acknowledging the very real warning signs is chef's kiss. The contrasting voices he hears in his head – one attempting to rationalize, the other a voice of intuition (Mina) – create a dynamic and engaging internal conflict.

Jonathan's internal monologue, fractured and increasingly fearful, is incredibly effective. The simple act of the Count taking his watch becomes a violation, a symbol of the Count's encroaching power. The chill Jonathan feels from the watch is a fantastic sensory detail that amplifies the unease.

The contrast between his outward politeness and his underlying menace is particularly effective. The Count exerts a subtle but powerful influence over Jonathan, both through his words and his actions. The forced wine drinking is a particularly unsettling example of this manipulation.

The internal dialogue suggests that excessive rationality can be a form of self-deception. Jonathan's attempts to explain away the strange events he witnesses only make him more vulnerable to the Count's influence.

The chapter hints at the importance of intuition and the need to listen to one's instincts. Jonathan's internal warnings are a sign that he is beginning to sense the true danger he faces.

Love the sense of suspense, mystery, and dread, and knowing what's coming makes me want to see how it will affect his mental state and his reactions.