Welcome

Jonathan stood in the new silence for a small eternity. His watch was unsympathetic in this estimate as checking it showed only a passage of minutes. He would have dared to call through the door if he believed his voice could sound louder than a sigh through the timber. There might be more luck if he pressed himself up against a window and yelled, supposing his voice reached any place where there were lights burning and people awake to hear his echo in the ponderous halls.

More minutes piled. The cold and the quiet did the same. There was not even a wolf cry to break the hush. Jonathan held so still in that silence that a moth found its way to him and rested on him as if he were a tree. He watched it crawl and thought with a calm he did not feel:

What are you doing here, Mr. Harker?

The moth moved to his heart, batting its wings against his pulse.

You don’t even know where ‘here’ is.

Another ripple of fear went through him as he recalled the fact. All the post from Castle Dracula had only ever come from a Bistritz service and even the most detailed maps had no position for it. All he knew for certain was that they had left by the Pass and driven up to the sky itself. The moon might scrape against the highest roof.

Jonathan scrubbed at his eyes and pinched his face until he might have bruised. No, not asleep. He stood precisely where he was, a shade of a solicitor at the door of a castle made ancient with unknown centuries, in the middle of a haunted night. Alone. Mostly.

“Do you have the key?” Jonathan whispered down to the moth. The insect gave no answer. He set his finger level with it and smiled as it crept over his glove. “Can you stay with me until morning? I doubt the driver will be back anytime soon.”

As soon as he said it, there was a sound of footsteps. A heavy tread that echoed on the other side of the door. The moth took off at the first step. Jonathan thumbed at the bit of dust it had left on his knuckle and peered as best he could through the narrow gaps of the wood. Here was an approaching light coming up to the threshold. Chains rang against each other while great bolts shunted out of place. A weighty key turned in a lock that might have been as old as the Carpathians themselves.

The door opened on a bodiless head hovering in the dark.

Or so it looked before Jonathan’s sight adjusted to the glow of the lamp. The latter was a thing of antique and ornate silver whose flame danced without any cover. It gave a temporary illusion that the figure before him was only a head floating against the castle’s lightless innards. In truth, he’d been fooled by the man’s choice of dress; from the throat down he wore nothing that was not black. Even the jeweled pin at his throat must have been obsidian. It made the glimpses of face and hands seem all the whiter.

It was a gaunt old face, belonging to a man almost a full head taller than himself. The pallid complexion was made snowier still by a white moustache and a stunning cascade of a mane that fell beyond his high shoulders. His free hand waved in a gentlemanly way, as if to show Jonathan inside.

“Welcome to my house!” the old man intoned with perfect English, but for its inflection. “Enter freely and of your own will!”

There was no further motion or word from him until Jonathan had dared to set a foot past the threshold. His sole had scarcely grazed the stone floor before Jonathan found his hand halted in the act of reaching for the portmanteau. The old man trapped it in his own hand with a strength that brought the driver’s grip to mind. He winced both from this and the shiver that shot up his arm. Even through his glove he felt that the old man was staggeringly cold.

Like shaking hands with a corpse.

“Welcome to my house,” the old man repeated, his grip towing Jonathan another step into the foyer. “Come freely. Go safely; and leave something of the happiness you bring!” There was a last tight shake before Jonathan’s hand was released. Again he thought of the driver, so faceless behind hat and beard. If this was not the same man he wondered if they might not at least be relatives. But the old man had called the castle his house, and so…

“Count Dracula?”

The old man gave a small bow and answered, “I am Dracula; and I bid you welcome, Mr. Harker, to my house. Come in; the night air is chill,” he turned and set the lamp in a bracket before stepping back out over the threshold, “and you must need to eat and rest.” At the last word Jonathan saw he had already snatched up the luggage on the step. He held them as easily as the driver had, as though they were not only empty, but made of foam. Even so, Jonathan felt his stomach flip at the idea of making an elder, let alone a client, a noble, play footman. He reached for both pieces.

“That’s quite alright, I can—,”

But the Count held both away with the ease of an older sibling withholding a toy from the younger, going so far as to somehow grasp the whole of Jonathan’s things by one lax hand. The other took Jonathan by the shoulder and spun him until he was facing back into the foyer, marching to keep pace with his host’s stride.

“Nay, sir, you are my guest. It is late, and my people are not available. Let me see to your comfort myself.”

“Please, I should at least take one or the other. I insist.”

“Ah, but I am host here, and so I insist back that you not weary yourself any further tonight. Unless you think to steal the traps from my hand, of course.”

Jonathan watched him dangle his luggage by his fingertips. There was no more protest as they walked on. And on and on. Forward and upward again as though they were scaling another mountainside. Down one great passage and up a twisting length of stairs and down another vast hall after that. Jonathan counted only a single flare of firelight apiece in each cavernous space, all from solitary lamps left burning. The greater share of illumination was provided only by the moonlight falling through the windows’ diamond framing. It was that peculiar dosage of light that seemed to thicken and redouble the shadows in a space rather than banish them.

The Count appeared so accustomed to the interior that he might walk it blindfolded. Though perhaps it was due in part to his footfalls. He seemed to almost hammer the stone floors and runners with his bootheels, echoing through the cathedral dimensions of the castle as though he might tell his place from the noise as an ordinary house might give its locations away by specific creaks in floorboard or hinge. Jonathan tried to soften his own steps as he kept an ear out for any others stirring in the halls. There was no telling where the staff’s quarters were or what hour they must have given up the wait for a single guest. If they slept close by, he’d just as soon not wake the whole house.

With this in mind, he cringed against the sound of the Count throwing another massive door open at the end of the passage so that the ancient wood groaned. But worry melted at once in the face of the new space. Here was a dining room that glowed with ruddy light. The broad mouth of a fireplace flared while walls, chandelier and table all flamed with candlelight. At the table’s far end he saw a place already arranged in expectation of supper. Gold gleamed in everything but the folded napkin waiting with its plate.

The Count paused just long enough to shut the door behind them, cross the length of the chamber, and throw open a second door. It revealed a room with eight sides, a single lamp, and no window at all. This led him to another door which he swung open as Jonathan came within a step’s reach.

Inside was a bedroom that might fit three, perhaps four apartments like his own. Its warmth was a match or better than the heat of the dining room, for a fireplace roared around a heap of fresh logs and the lamps were all lit so that what shadows remained in the room sat politely in their corners. More, they revealed a magnificence of trappings and size that Jonathan had seen only in the artwork of fairy tales. A bygone majesty was stamped in every fabric and furnishing that met the eye. Had the Count not been present, Jonathan would have pinched himself again. The Count laid the luggage inside the door and retreated back into the octagonal room.

He smiled as he said, “You will need, after your journey, to refresh yourself by making your toilet. I trust you will find all you wish. When you are ready, come into the other room, where you will find your supper prepared.” Then the door was shut and Jonathan was left still half-stupefied by where he stood. Absurd as it was, he felt the beginning of tears pricking at his eyes.

“Come now, none of that,” he almost laughed as he ground his knuckles against his lashes. His gloves were still on. Hat and coat as well. He shed them gladly and took himself to the room conjoined with this one, finding a grand if somewhat medieval lavatory. The bathtub looked as big as a pond to him. It was almost distracting enough to overlook the one thing missing in the space.

No mirror?

He actually stared at the empty space where a looking glass ought to have hung, as if his vision had simply not caught it on the first look. But no. There was simply no mirror. Nor was there a glass in the bedroom. Jonathan dug out his toiletries early and his shaving glass with it. He found himself a trifle bloodshot, but presentable enough once he ran a brush through his hair. Hawkins’ gift still sat well on him from head to toe. And in his breast pocket, still pressed flat by the journal, was Hawkins’ letter.

“Alright. It will be alright.”

So he told the letter, his shaving glass, and the room itself. Jonathan strolled out through the octagonal room and, with a breath held, back into the dining room. Supper was arranged around the table’s far end with many a covered dish waiting and the tall chair pulled out. Not the head seat, he noted, but the one directly to its side. The Count had not yet taken that throne. Instead he stood beside the fireplace, apparently lost in thought before Jonathan entered. He waved at the laden table.

“I pray you, be seated and sup how you please. You will, I trust, excuse me that I do not join you, but I have dined already and I do not sup.”

“Thank you. But first I must make a delivery.” Jonathan offered him the letter with the firm’s seal. “From my employer, Mr. Hawkins.” Count Dracula eyed it with some surprise. For a moment it seemed as if he had never seen an envelope before and distrusted the look of the stationery. That gravity held as he opened and read the single sheet within. The dark look softened into a pleased grin.

“I believe this is better meant for you, my young friend.” So saying, the Count turned over the letter to Jonathan with a sharp nail aimed at a specific passage. It was one that elated as much as confused.

I must regret that an attack of gout, from which malady I am a constant sufferer, forbids absolutely any travelling on my part for some time to come; but I am happy to say I can send a sufficient substitute, one in whom I have every possible confidence. He is a young man, full of energy and talent in his own way, and of a very faithful disposition. He is discreet and silent, and has grown into manhood in my service. He shall be ready to attend on you when you will during his stay, and shall take your instructions in all matters.

The missive read as a fine pitch to any doubter who might have expected a senior professional rather than a green young replacement. Of that, Jonathan was relieved and proud. Yet it was strange to think the note was necessary at all, for:

He called me Mr. Harker at the door.

The obvious reason was that Hawkins had sent word to the Count of the change beforehand. A reminder, then? A reassurance? Before Jonathan could dwell on it, he found himself being ushered to his seat by the Count. His host lifted one of the golden covers to reveal a plump roast chicken, still steaming on its plate. It was joined by a sumptuous company of salad, rolls, cheeses, and a scatter of elegant little additions. In place of water there was a large bottle of Tokay wine. He would go on to have two glasses of this, each poured by the Count himself.

It was after he took his first sweet taste of this that the Count took his great carved chair and said, “Now that you are here, I fear I must put you to work at once. If only to report to me as the scout might. Tell me, how was your journey to Transylvania? I have not travelled far from my mountains in many years and should like to judge what my way to fair England shall be like. I ask that you spare no detail.”

“The route you plotted went very smoothly, Count,” Jonathan assured over his glass. “The only trouble was in the timing of trains and coaches being held up. But as you wrote, that was likely the fault of holiday delays. I imagine it will be far quicker travel for you once you depart. And,” he smiled as he raised a forkful of chicken, “should you go along the same way, you shall never be disappointed in the way of cuisine. I have been gathering up recipes to bring home all the while. If the people manning your kitchen would allow it, I should like to interview them for their steps in preparing this.”

The Count grinned at this, nodding as he assured, “I shall see to it that you will know any and all culinary secrets of the castle before our business is done, my friend. But back to the travel itself; my driver spoke with me upon arrival.” The Count was now half-bowed over the table with elbows braced upon the wood as his chin rested in the nest of his woven hands. As he did, Jonathan saw the same rosy illusion of firelight reproduced in the old man’s eyes. Where the lamps had tinted the driver’s stare crimson, so too did the hearth make the Count’s eyes burn. “He is a native of the land where you, playing the good visitor, are too kind in judging the peasants for the consequences of their fears. To speak plain, I know you were nearly absconded with this night. All for the sake of quailing before an unlucky date on the calendar. Is this not so?”

Jonathan swallowed his mouthful dryly.

“I hesitate to put it exactly in those terms, Count. There was no ill will in any of my experiences in coming to you. At a guess, I think it must have been concern for travelling up by night that worried the coach’s driver. Your own man must be a fellow of extreme skill to have maneuvered as he did with the moon barely present.”

The wolves would certainly vouch for him.

He helped himself to another sip of Tokay as the Count’s stare shined. Jonathan realized he had yet to blink.

“That he is,” the Count allowed. “But again, I know my land and my people as a father knows the foibles of his children. Just as I know that, though they respect my title and my patronage, you doubtless caused a stir of great anxiety and wringing of hands when the people of Bistritz learned your destination. Pray, do not deny it—I know it from experience. Indeed, I have learned so from guests hosted in the past. The last was a foreigner as well, and was not shy in his shock at how ardently his company in the Carpathians held to the foolish fears of dead ages. Unless the country has all at once given up those inherited dread in support of the enlightenment rolling towards us with the new century, I assume you must have crossed the same fretting yourself..?”

Jonathan thought of the entire coach screaming as though Hell itself were pouring its horsemen out of the Pass. Jonathan thought of the gifts and prayers foisted on him and still hiding in his bags. Jonathan thought of the crucifix resting against his heart. Jonathan thought of an old woman’s desperate terror and grief. Jonathan thought of a costumed woman on the train tracks, out seeking Death on a hallowed evening.

“I did,” Jonathan admitted. “But I merely took it all as a matter of course for the sake of the holidays. England has its own times of fervor and pageantry.” The fingers of his left hand crossed under the table. “In truth, I did not heed the spectacles as anything more than similar, if far more robust, performance. The only occasion I felt an act went nearly too far was not here, but back in Munich.” The Count raised one of his heavy white brows at this.

“Oh? What act was this?” Here Jonathan regaled him with the sight of the actress in her burned gown and the shock of the lightning bolt which had struck more fear into him than if the woman had truly been a ghost. The Count waved this away with a chuckle. “She was either a spirit or a very lucky member of the living. You would have known had she been struck. The smell would have given her away.”

“The smell?”

“Her flesh, her hair. Had she been struck, the reek would have lingered even if she had magically hobbled away. It would have made a very thorough performance if so.” Here the Count unfolded his hands in an airy gesture. “So dedicated to the role of Lenore that she would die for it. Certainly she was quick enough to avoid the bolt.” A sharper grin curled under the white moustache, baring the redness of his lip. “Denn die Todten reiten schnell.”

“Laß sie ruhn, die Todten,” Jonathan answered back. He tried to smother the sudden chill in his stomach with another taste of the Tokay. It only worsened as the Count’s eyes seemed to flash anew by the firelight.

“You know the whole of the ballad?” he asked.

“It is likely the only German I can trust myself with without turning to my dictionary for confirmation,” Jonathan confessed.

“The English as well?”

“Yes, though I prefer Bürger’s original cadence over the translation.”

The Count’s eyes narrowed as he pressed, “And what of the story itself?”

Jonathan paused in the act of tearing a piece of bread, wondering if there wasn’t some test hiding in the question. If there were, he could not place it. He wished the Count would blink.

“I enjoy it as any well-made tragedy can be loved.”

“Is it a tragedy? The final verses suggest the chance of forgiveness for poor Lenore’s blaspheming in her death. Or perhaps I misremember.”

“I do not believe so. Lenore did blaspheme by technicality in cursing God for letting Wilhelm die. That her soul can possibly find forgiveness in the afterlife seems a lopsidedly small charity when Death itself went out of its way to trick and slay her simply for grieving and being irate that the omnipotence she put her faith in did not protect her beloved. The moral of the ballad suggests being angry with God for allowing cruel things to happen equates a sin worth being killed or even damned for. I find it difficult to paint such a narrative as anything other than miserable.” Heat roiled in Jonathan’s face as he muffled himself with bread and wished for a glass of water to drown himself with.

Such winning conversation, Mr. Harker. Truly you are a fountain of high-minded religious and literary opinion. Are you not an English Churchman? Do you not have the Cross itself gifted and hidden in your shirt? Do not touch another drop of the grape, for God’s sake.

Determined to follow orders, Jonathan slid the third-full wineglass out of his reach with apology hanging on his face.

“Forgive me, Count, if I have made any offense. I did not mean to—,”

The wineglass was stolen up and refilled before he could finish.

“My friend, you make no misstep. I pry only because I feared you might be of that dense number who fear that empathy for the doomed Lenore would deliver divine punishment. Your mind and my own are quite agreed on the brutality of the ballad’s supposed lesson. It is a fearful thing to imagine, no? In this age, the faithful are taught that He is a holy force of love, of protection and forgiveness. But Gottfried, he harkens back to the Lord’s original callousness. His roots of jealousy and demand for fealty above all else; the God who cursed faithful Job and was almost too late in calling off His demand that Abraham slaughter his own child. That is the God who sends Death to punish Lenore, whose only sin was that of an ant cursing the boot that crushed her fellow insect.” The Count set the filled glass directly between Jonathan and his plate. “Am I correct in thinking you speak from experience?”

A cemetery came and went behind Jonathan’s eyes. That grey-black mourning landscape seen from the height of a man’s hip. Two graves open and waiting to be fed.

“Experience of a kind,” Jonathan murmured. “But it was of a very different sort and long ago besides. In any case,” he twisted the wineglass by its stem, watching the vintage turn to a whirlpool, “I fear I’ve quite derailed from your original query. I have not even reached the Hotel Royale.”

Jonathan spoke of rooms and trains and coaches and kind people as wine and supper ebbed away. When plate and glass were empty the talk moved up beside the fire. Jonathan barely had the plush new seat under him when the Count opened a gilded case on the end table and revealed a wealth of cigars whose price might have paid for a month’s worth of meals.

“Please, enjoy these as you will,” the Count insisted, plucking one free and pressing it into Jonathan’s hand. “I do not smoke, though the scent pleases me.” Jonathan paused in digging out his matches as the Count produced an ornate lighter of his own. He would not hand it over, but lit the cigar as it balanced in Jonathan’s teeth. “It has been some time since I could accommodate the burn of it. I am glad they shall not go to waste.”

“Not so glad as I am to put them to use.” And it was true. He did not smoke overmuch as a habit. To smoke or drink cost one in money and mind, and so such indulgences came rarely. Even then they brought little pleasure, having to buy cheaply. “Thank you.”

“You may thank me by returning to the subject you dangled and discarded before returning to talk of travel.” The Count angled in his chair so that he faced Jonathan directly. This near to the fire, the entirety of his eyes flamed bright. “Your thoughts on poor Lenore, her plight under a capricious God, and the soldier He made of Death are most refreshing in a land that, though beloved, stings somewhat in its sanctimony and superstition. Such is part of the reason I have sought another abode among the modernity and sense of your England. I can only hope the country brims with people akin to yourself.”

The Count’s legs crossed as he spoke and his white hands settled upon his stacked knees. This he did fully in the hearth’s light, flaunting details so far overlooked. Though his digits were long, there was a broadness to them and their knuckles that made Jonathan think they had been hammered into a human shape from a beast’s old form. His nails were sharp as spades on every finger. And, strangest of all, there seemed to be a downy patch of hair in the exact middle of the palms like a speck of animal pelt. The sight was not helped by the worrisome pallor that stood out there as much as above the man’s neck.

White, but not in the way of one who was merely pale or anemic. There was something in the tint that spoke of a body held just at the brink of decay. A greyness sat under the white that would be more at home upon a cadaver. Only the red of the exposed underlip suggested the presence of vitality and the old man’s mouth disquieted on its own. Its grin seemed fixed more as a leer, the teeth boasting a peculiar sharpness and length. The canines hung like stalactites.

Jonathan tore his gaze from this view and tossed it at the fire.

“I cannot make promises on that point, Count. No more than I can speak for any others’ opinions on the horror presented in the ballad’s conclusion. I will say it is not a religious fear, for my part. It can’t be. If I believed that literature using faith as its framework equated Scripture, then I might fall down screaming at the concept of Andersen’s fairy tale of, “The Red Shoes,” or curse the Almighty after finishing Paradise Lost. To that end, I would not be able to enjoy any play or book with a fantastical element, as I would trap myself into railing against the heathen contents as some insult worth deeming evil for even existing as a fiction.”

Count Dracula nodded and hummed at this. A long white lock moved out of place as he did, showing an ear with an impressive point at its top. It folded almost like a bat’s.

“It is a pleasure to know that there is hope yet for new generations to shake off the fretting of elders who cling to stubborn ignorance and call it faith. I have done what I can to make an exception of myself, making friends with the printed word more than my own countrymen. I have been as encouraged by what I read as I have grown sad at how little the people of my land will accept of the world as it exists today. And tomorrow’s advances in literature? The sciences? Discovery itself?” The strange hands gestured together as if to wash. “There is no room at all in them for that.”

Jonathan kept his mouth plugged with the cigar. It felt safer to have it in the way of himself.

Does he think so little of them?

“I doubt it is so hopeless as that,” he tried. “The traditional and the contemporary can coexist.”

The Count bent closer in his seat. Near enough that Jonathan could catch a puff of his breath when he spoke; a sweetly-sickish carrion smell.

“Ah,” a sigh that reeked of decay, “that has the sound more of wishful thinking than experience.”

Jonathan nodded his head low to school his face as he admitted, “Possibly. I cannot deny that clashes are inevitable between the old and the new, but on the whole I believe progress relies upon both. That is, keeping hold of those traditions and beliefs that are the best practices while advancement tries to see what will last well enough to be tomorrow’s idea of traditional.” Jonathan tapped the ash away and tried to laugh. “All of which is several leagues apart from talk of grim poetry. My apologies for steering us so far off-topic.”

The Count shooed the words with his hand, huffing, “You need not apologize any more than Scheherazade might ask forgiveness for keeping her Sultan’s ear. It has been too long since I have had conversation that does not feel like the gathering of dust on my mind. I have said all that can be said and heard all that can be heard when it comes to my people. Although I must wonder why it is a young man such as yourself ducks so artfully from talk of a story in which one lover loses the other to a grim fate…”

A glance was made to Jonathan’s left hand. Jonathan switched his cigar to it as if it might disguise the bare ring finger.

“It is an affecting story to me for more than one reason,” Jonathan spoke in the direction of the hearth, the floor, his shoes. “I have known a bitter loss in the past. Lenore’s words and my thoughts were mirrored for some years as a boy. But that is the past and I have outgrown it.” A genuine smile curled despite himself. “Instead, it is a present joy that makes me love as much as dread the work.”

“For a present joy could be tomorrow’s loss,” the Count concluded. “Such is the caveat when one finds love.” A moment passed in which the Count’s face relaxed in a musing way. Jonathan took the chance to look at the man’s own left hand and felt a pang at seeing his was bare as well. But the old man’s softness gave way to something nearly impish as his head canted. “And now I must play the pest and ask, how soon until this present joy is wedded? Unless this is a joy newly met.”

“We have known each other for many years and courted officially for the past few.” Jonathan beamed down at the cigar that now twisted in his fingers with fidgeting giddiness. “I proposed to her a month ago. We plan to marry before the year is out.”

The fact of it washed through him like a cleansing stream. A reminder that dimmed all the fears and questions of the night down to their proper form. It was a temporary strangeness he found himself in. One that had proven to be halfway magical in hindsight. The journal would seem like so much invention to Mina’s eyes were it written by another.

“I suspected as much,” he heard close to his ear. Again the carrion scent rolled thickly over him, driving back the pleasant perfume of the smoke. Jonathan started at realizing the Count’s chair was empty. He froze outright when he saw tendrils of the man’s white hair hanging past his own shoulder. The Count was behind the chair, bowed over him like a leaning tree. Jonathan twisted to look up just as his host’s hands came down to rest on his shoulders. The cold of them sank through the suit. “It is never long before those of your like are found out and stolen away to the altar.”

The hands moved on him. Jonathan shuddered as if he might shake free of the suit and his skin. His face fumbled its schooling and showed too much. Not nearly the whole of his shock or his discomfort, but a fraction was apparently enough. The Count drew away and back to his own seat, moving leisurely—yet without taking his eyes from Jonathan’s face. Even his grin became strangely immobile as the lips peeled up and back in a parody of mirth. It was a rictus that showed the fullness of the bright teeth and their uncanny shape. This Jonathan saw only in the peripheral.

His eyes were trapped by the Count’s.

Jonathan would try to convince himself later that he had committed only some sin of decorum and perhaps nodded off. That he had half-dreamed the strange period that followed. This he would fail to believe. His eyes had been open, his mind awake. Both caught and held by the lambent grip of the Count’s look. And they were lambent. Like the quirks of skin and teeth, Count Dracula’s eyes seemed to carry an inner vibrance that turned the reflection of the firelight into their own small infernos.

Yet they made him feel cold. Colder than the night. Colder than the white hands. Jonathan thought blearily that the Count must have mistaken him in some way; that they were engaged in a wordless game or test which he was himself oblivious to. A world away, he felt his mouth try to open. To make a question happen.

No questions came. Not a single word.

The Count’s smile somehow grew wider as he leaned forward and tweezed the last nub of cigar from Jonathan’s hand before it could burn its way to his fingers. He snuffed it in the glass tray without taking his gaze from Jonathan’s. Without offering his own voice to end the quiet. Even the crackling of the fire had become muted. Jonathan scrambled to catch hold of decorum as a lever; he should not stare, should not let this silence unspool so clumsily, should apologize—

For what?

For anything. Just speak. Close your eyes. Do something to break this. Before…

Before?

Ruining whatever rapport you’ve built with the client, for a start. He is the host and the buyer and a noble and you clearly must have insulted him in some manner. So do something! Anything!

But for all the panic winding itself up in his skull, the Count seemed entirely at ease in the hush. More than that, there was an element of amusement drawing at the gaunt face as though he were watching the opening of a beloved play. They might have sat that way for an hour. Staring. Waiting.

Wanting.

What?

Wanting. Yes. I want something. We both want something. What is it?

The Count’s head tipped slowly to one side. Jonathan moved his head in time with him, deft as a reflection. His eyes no longer burned. He was not tired, but he was calm. Everything was. Yet he still wanted something. Wanted…wanted…

Though his stare never broke from the Count’s, he found his head suddenly filled with the image of the old man’s mouth. His teeth. Whiter even than the snowy wilderness of his hair. Long and sharp as icicles against the scarlet lip. Smiling.

Yes. Smiling. Wanting.

The Count righted his head. Jonathan stayed as he was, his neck still taut at its wondering angle. Even when the Count’s eyes broke the staring contest to observe something—Jonathan’s shirt collar? His tie? It did not matter.—Jonathan still could not budge himself or his eyes or his mind. Which was quite alright, of course. He was calm.

Heart my heart going so fast too fast something is not right something is not—

Wanting. Calm. Smiling. He is smiling. You should smile. You should—

Up up up wake up something is wrong something is—

Want to be calm. Want to smile. Want him to—

No—

His teeth—

No no this is not me not mine no—

Yes, want his mouth, want his teeth, want—

The sound of wolves pierced the air.

Jonathan jolted in his seat. The wolves’ howling choir rang on and on from the valley below. Here, finally, the Count closed his eyes with a sigh.

“Listen to them—the children of the night. What music they make!” He turned again to Jonathan and must have seen something lacking in his countenance as he clicked his tongue. “Ah, sir, you dwellers in the city cannot enter into the feelings of the hunter.” Saying so, the Count stood from his seat and strolled to Jonathan’s. “But you must be tired. Your bedroom is all ready, and to-morrow you shall sleep as late as you will.”

One hand floated out, the white palm and its spot of pelt waiting. Jonathan laid his hand in it and fought down a shiver. Though any twitch of his might have been missed with how easily the Count hoisted him from his chair. The grip shifted up to Jonathan’s shoulder in a hooking way, guiding him back to the door of the octagonal room.

In a contrite tone the Count sighed, “I have to be away till the afternoon. So,” he gave a nodding bow as he held the door open, “sleep well and dream well!” His hand prodded Jonathan in.

“Likewise,” Jonathan managed back. He smiled through the word. The smile held until the bedroom door was closed between them, at which point the expression fell and shattered like porcelain. His heart pounded as if abused by some mad drummer. He could still taste spice and poultry and smoke. Sated hunger and any mote of fatigue had been burned away by the riot of confusion and thrill threading through him. This time he did not bother to pinch at himself. He was awake.

And what did that mean now? What did that make of all that had transpired between the gift of the crucifix and the door of the borrowed bedchamber shut at his back? What?

The plainest answer is that you do not know. All you can do now is put it to paper. Whether your senses have made an error or you have found yourself neck-deep in eldritch unknowns, a record keeps memory from reworking events into false proportions. To your tablets, Hamlet.

Jonathan surprised himself with a thin bark of a chuckle. Then he took himself to the stately writing desk that stood waiting beside a high window. Through the glass he could see that the night was washing out as sunrise crept along. Too awake, and yet too muddled to uncap his pen, Jonathan laid the journal on the varnished table and made himself busy with his luggage. The toiletries were already laid away and his shaving glass now hung by a smaller window by the tub. He set aside the paperwork and reference material reserved for the transaction, arranged his clothes and shoes in the wardrobe, and, lastly, determined what to do with the bounty of odd gifts his brief friends in the coach had pressed upon him.

The wild rose he tucked under one of the pillows resting on the veritable lake of a bed. The sachet he kept in his overcoat’s pocket. Other oddments were stored in the same corner as his memoranda or, in the case of the garlic blossom and mountain ash, taken to the windowsill. The starry white flowers and the rowan sprig were braided close with thread, making a small bouquet. He might have hung it from the wall, but he recalled the Golden Krone had sported similar garlands around its windows. Smiling, he wedged the charm into a groove between two large stones near the pane. Done.

Except…

Jonathan returned to the desk and opened the journal to its back cover. Saint George still rested in the leather flap.

“Today is your day, George. Watch for dragons.”

He took up the pen and began:

5 May. The Castle. — The grey of the morning has passed, and the sun is high over the distant horizon, which seems jagged, whether with trees or hills I know not, for it is so far off that big things and little are mixed. I am not sleepy, and, as I am not to be called till I awake, naturally I write till sleep comes…

The use of shorthand did little to save time. Once he reached the final lines of the entry—

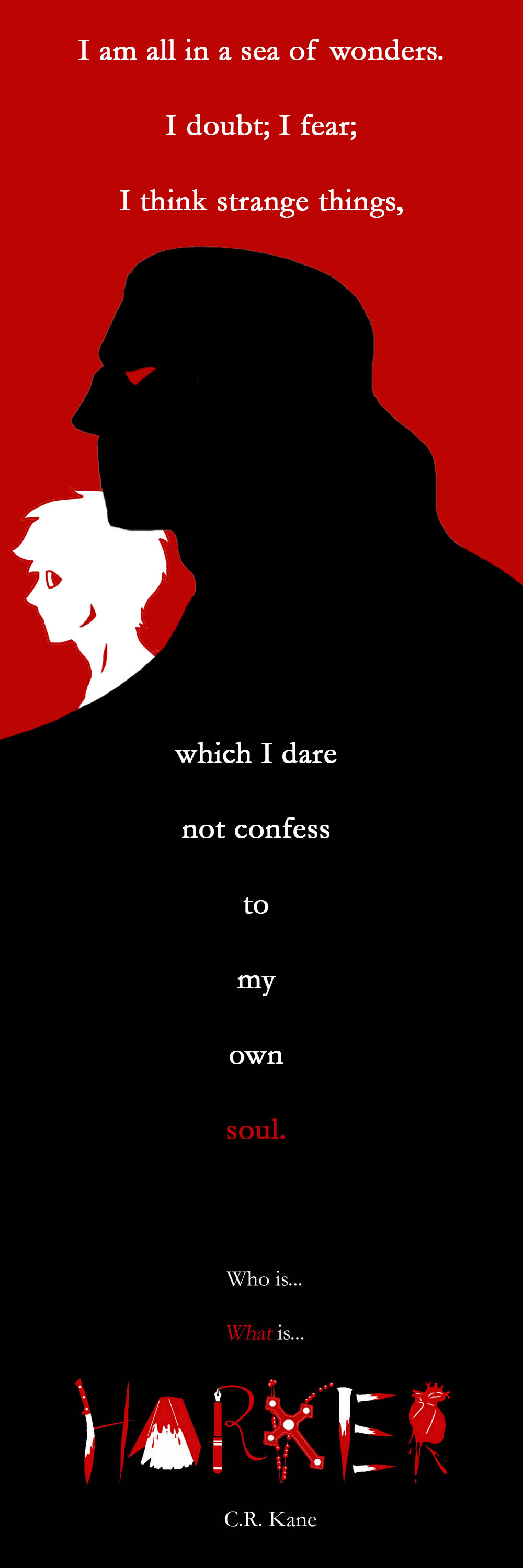

I am all in a sea of wonders. I doubt; I fear; I think strange things, which I dare not confess to my own soul. God keep me, if only for the sake of those dear to me!

—the sun had risen high enough to be out of sight from the window. Dawn was past, now there was day. The glimpse of beauty shown through the glass did much to sweep away the worst of the aforementioned wonder and doubt. It was far harder for the imagination to betray its owner by daylight.

Insomuch as imagination can be blamed for anything last night. Of course, now that it is bright enough, you’re too tired to step out and get a decent look at the grounds.

He shut the journal and stifled a yawn.

Ah, well. There’s time enough later.

The journal found a home under his pillow alongside the wild rose. He surrendered to another yawn as he changed out of the suit and into his nightclothes. Should he leave the ensemble out for someone to collect?

How long will you even be here, really?

The suit wound up back with the stowed overcoat and fine shoes. He almost hung the crucifix up with it. Instead, it came to bed with him.

It did not join him in his dream.

Mina had half her childhood split across Ireland and Scotland, passed along a chain of auxiliary caretakers for lack of living parents.

She might have been there still but for discovering that her father’s only cousin lived in England and had better means than her then-current borrowed household. Mina had been sent away to him with only her stories of those early lands carried off as positive memory.

“My father’s, mostly,” she’d told Jonathan. “There was more of Ireland in him and more of Scotland in my mother, and flints of other nations all sprinkled through them. A grandmother was German and I wear her name. A great-grandfather was Egyptian and I carry a ghost of both his face and his race. Mine is a medley of bloodlines that I arrived too late to meet. I was still an infant before my parents left the world, but before that they wrote. Perhaps they thought to chase after the Grimms’ legacy, preserving old tales before people forget to share them by speech. Some of my favourites were the ones of animals that were not animals. Horses especially. I think everywhere must have some kind of old magic story to do with horses, or things masquerading as a horse. One that scared me most, and made me love it all the more, was the púca.”

The púca, a creature of many forms, as prone to evil as granting favors. One of its preferred tricks was taking the shape of a black horse and stealing riders away into the night. Sometimes the riders were seen again, ragged and abused, but alive. Other times they were simply gone.

“Gone? Gone how?” Jonathan had asked—was asking, now, back in the dream of the park. They had been caught up in admiring the sleek ink-dark mare pulling along a pretty victoria.

“In any number of ways,” Mina said, still watching the black mare as the victoria’s customer departed. “Perhaps they died. Perhaps they were taken away to the place under the hills. Perhaps they were cursed into some new shape, like the enchanted victims in fairy tales. I suppose it depended on the púca’s mood.”

The victoria came their way. Mina had let Jonathan take her arm so that she might steer them along; an allowance she always blushed to make, even when well out of sight of her students or relations of the same. But here, in the dream, there were no blushes. There was only the sudden grip of her palm over his as she led them. Her hand was cold. Crushing.

“To the chapel,” Mina told the driver. Her voice sounded strange. Musical, but in a brittle way. Glasslike. But what did it matter?

“To the chapel,” the driver said behind his dark beard. He had no more of a face in the shade of his hat. Apart from the sharp flash of his teeth. And his eyes. His eyes were…

“Wait. Mina, wait.” Mina did not wait. Nor did Jonathan. Nothing of him obeyed himself as his hands slipped from her and his feet took him up into the victoria. Mina did not join him. He only felt the chill of her hand as it helped him up and shoved him onto the seat. The door closed without either of them touching it. “Mina—,”

But Mina was not there when he looked. Even the park was gone. As was Exeter and the daylight itself. All of the sunlit world had been replaced with a cemetery that reached out into the horizon, seen only by the glow of a leering moon. The victoria lurched forward. Jonathan saw that the driver had disappeared. It was only the black mare pulling him on and away. The horse’s eyes burned enough to leave a streak of scarlet light as it plunged through the night and past the leaning headstones. Onward, upward, further, further. The cemetery had been made on a mountain and the road was lined with blue flames.

“Stop. Please, you must stop.”

To the chapel, came a voice from the mare, from the graves, from the dark itself. To the chapel.

The victoria raced on. Its destination loomed close. But before Jonathan could tell whether it was chapel, castle, or crypt, his dreaming mind fell away completely.

To keep reading, go here:

Dang he's pulling out that mesmer nonsense on the first night! (Though I suppose dinner was provided first).

Between all the delightfully chillh spookiness going on I must admit I chuckled a good deal on Dracula going "oh yeah the coachman's an excellent driver. Fantastic guy. :)"