Travel Fast

“Young Herr?”

Jonathan looked up from his table. He had requested another helping of robber steak and was nursing a second glass of Golden Mediasch. The latter carried a sweet sting that didn’t seem to do much in the way of easing his nerves, but was pleasant all the same. The landlord and lady smiled down at him.

“Yes?”

“I have received word from,” the old man’s weathered face seemed to fumble its expression as he searched for a German approximation, “from your host that I am to order the best seat for you when the coach arrives. Three o’ clock, recall?”

“Three o’ clock,” Jonathan nodded. “Thank you. But you say you received word just today?”

“We did.”

“Was there any new detail? That is, was there anything more I should know?”

Why send a second message only to confirm what was already known? Reiteration seems a stretch.

The landlord shook his head. His smile held on more valiantly than his wife’s.

“No. No other detail. Just the seat. Money was sent with the letter. That is all.”

“Do you know Count Dracula personally? He sent word through my employer that he picked the Golden Krone especially for my last stop before reaching the castle. I remember he described this place as his first recommendation to his visiting friends on the way to the castle.”

Both halves of the couple paled several shades. The landlady actually seemed to tint green as she exchanged a frantic glance with her husband. Both of them made a reflexive sign of the Cross over their hearts. Still, the landlord held rigidly to his smile as he shook his head and gestured in pantomime of confusion.

“Young Herr, forgive me. I do not understand.”

“Count Dracula,” Jonathan tried again. “Castle Dracula. Are you familiar?”

There was a shaking of heads and a muttering of apologies before the couple hastened away. His landlord did, anyway. He had to hook his wife by the shoulders before she joined him in his gait. As Jonathan frowned after them, he saw his fellow guests all ducking their gazes away. Many were among the number who had sat with him by last night’s fire. Staying up, awake, aware.

Aware of what?

Jonathan finished his glass quietly and returned upstairs.

He had waited to change into the new suit as insurance against stains. A moment was spared to eye himself in the hanging mirror, as much to fuss with button and tie as to admire. But the tailoring failed to hold his attention for long. Not when there was so much to consider above the neck.

How much had Hawkins told the Count of him? Had he mentioned him at all? The notes he’d received thus far had never called him by name. Any belated explanations had to be waiting in the letter that now sat secure alongside his journal in his pocket.

And if he takes one look at you and turns up his nose? If he thinks himself defrauded when a young man appears in place of the old professional? If he sees your face and wonders if he has received an Englishman at all?

Jonathan ran his hand over a shaved cheek. His fingers traced the places Mina would have walked hers as he tried to summon up her voice in his head.

You came upon the right thought back in the station, Jonathan. Even in the library! This place is not England’s stiff island. It is a crossroads of sundry races and as many histories. What dour looks have you received here except from tourists? Even they softened upon hearing you and your hearing them. The people here are good. And if the Count proves to be an exception, then he is hardly a worthy client. Certainly not one that Mr. Hawkins would do business with. You know he will not blame you if the man is so churlish as to fuss over his solicitor’s heritage to the point of ending the transaction.

But what of the rest, Mina? he wanted to ask. What happens if I fail you and Hawkins on my first assignment? What if it’s a prelude to a career that dies before it’s born? What if Hawkins wishes he’d sent Bentley after all? What if I am going into this without everything I need? Without knowing all I should know?

Mina’s voice rebutted, You have all the paperwork. You studied all you could at home and have taken in all you can abroad. What more is there?

Jonathan didn’t know. But his lips moved of their own accord, mutely reciting:

“Better to be aware. Better to beware.”

Of what?

He screwed his eyes shut and laid his hands over them.

“Stop. You must stop.” These were more familiar words to him than any other. He had heard them in exactly three voices over the course of his life. His aunt’s, her husband’s, his own. If his parents had ever offered the same reprimand, he was too young to recall it. But the words were there for his own good. They were a recitation that held back the whole of him and strained out only the best. And if his best was not organic, the words could hold him in place until he crafted some finer self out of ether.

He would succeed in this task. He would because he must. That was the whole of it. To consider otherwise was not permitted.

And if there is more to consider than your work?

Jonathan’s hands dragged down until he met his eyes in the mirror. Darker than face and hair both, but of that shade which flared like cognac against a light. They might have been the gaze of a hart. A hare. A wild dog deciding whether to run or bite or let the reaching hand lay itself on his head.

It isn’t the task ahead that has you afraid. You cannot put a name to it. No more than any animal who smells the huntsman coming would know what to call him. But you feel it, don’t you? You have seen it. Heard it. Collected signs in piecemeal fashion that something is not right in all this. You don’t even know where you’re going. Castle Dracula exists in an unmapped pit among the Carpathians. And if something happens…

What? What could happen?

Jonathan had no answer for himself. This did not hearten him. At the same time, it bolstered the refrain:

Stop. You must stop.

No, he did not have a name for whatever shadows the periphery of his mind now fretted over. But there were names to spare for all the very tangible concerns involved with fumbling his first assignment as a solicitor, across the Channel, gift-wrapped by his mentor, every expense paid by an aristocratic client and host, just prior to the planning of his wedding day. With such things in mind, Jonathan assured himself that if Mephistopheles greeted him at the castle’s doorstep, he would smile. Jonathan pulled his hands away and found the proof of his smile waiting for him. The one he reserved as a default for the most caustic encounters and direst workdays. It was scarcely different from his truer expressions, product of practice and emergency daydreaming that it was. A thing fueled by a schooling of countenance and an internal hoard of buoyant thoughts.

He would meet the Count and all would go well. He would complete the transaction of Carfax Abbey with nothing amiss. He would record every heartbeat worth sharing for the journal. He would come home to Mina before the month was out, her face a haven in the crowd at the London station. He would lay a feast for them at his little table, gleaned from the recipe book patched together in his memoranda. He would make his vows and taste hers on her lips as the wedding bells rang. He would do all this and more, for it was waiting for him, patient and perfect on the other side of a last coach ride. Thinking so burnished his expression until it glowed. It clung in place when he heard a quick knock at his door.

It vanished the moment he opened it to see his landlady.

He almost failed to recognize her. Grief stamped her face so deeply it seemed to have gouged itself deeper than the wrinkles at eye and cheek. Jonathan thought sickly of the Grecian masks of old, all carved to the extremities of emotion for their actors. The old woman’s face would put to shame any artist who tried to depict anguish.

“Must you go?” she wrenched out in strangled German. “Oh! Young Herr, must you go?” She made it only this far before some straining fissure in her burst open and a tide of tears and pleading poured out. This she did in a language Jonathan couldn’t guess at. His own German felt thick and hobbled on his tongue as he asked what was wrong, what did she mean, what could he do, among a dozen other half-memorized fragments as he braced her just short of falling on him in throes so miserable he wondered how no one had come into the hall to gawk.

“I am sorry,” he said through a lull in which she had to stop for breath, “I must leave. My business calls me out and it is business for another’s sake. I must go.” The words felt oddly poisonous to him now. Her look as she peered up at him from under the puckered brow, eyes bright as glass, did not help. “Please. If there is some trouble I should fear, I would like to know.”

She seemed to war with herself. There was much she wanted to tell and the words for all of it were nigh visible on the thin lips. Yet her stare seemed to read something in him that forced the bulk of them back down her throat.

“Do you know what day it is?” she finally asked in enunciated German. The question was hoarse.

“The fourth of May,” Jonathan answered. The landlady shook her head in a grim way.

“Oh, yes! I know that!” She gripped at his sleeves all the tighter. “I know that, but do you know what day it is?”

“I do not understand.”

“It is the eve of St. George’s Day. Do you not know that to-night, when the clock strikes midnight, all the evil things in the world will have full sway? Do you know where you are going, and what you are going to?”

No. I don’t.

Jonathan beat the thought back from his lips and smothered it.

Aloud he could only say, “I was not aware the date landed so near to Walpurgisnacht here. If it is a comfort, I will not be drawn astray by any ill powers if I can help it. My time is not my own here and so I cannot afford to leave the route left for me—,”

The effect of his words was as immediate as it was painful. All the gathering dew on the lady’s eyes overflowed like waterfalls streaking over the crags of her face. Her hands left his sleeves as she buckled to her knees, her palms coming together in plea and prayer.

“Young Herr, please. Please. Do not do this. Do not go. At least…” her voice hitched and Jonathan felt the splintering of it in his chest, “…at least wait two days, even one, before you depart. You must do something, anything to hold it off. Please!”

Discomfort bordering on nausea twisted in him. The words of tourists and paper guides and more than a few lighthearted derisions overheard in Exeter all tried all rotted away in his memory. This was not mere superstition before him. He was looking at terror. A fear made with not just belief, but the old woman’s recognition. Something wretched had happened on a past midnight as the holiday turned over. In him she saw its encore approaching.

Jonathan got down on his knee and tried to raise her up as he said, “Thank you for worrying. But it is not my choice. I am dutybound to others. It is imperative that I see to this work. I am sorry. I am sorry.”

And you really are, aren’t you, Harker?, a phantom of Bentley intoned. You smell the trouble on this like a jackal catches wind of a carcass. That something your Gurkha side passed down or does it hail from dear Mum of Araby?

Before his mind could strangle the intruding voice out, the landlady rose on her own. One hand dried her eyes while the other went to Jonathan’s shoulder. Though it had no strength in it, the soft palm managed to keep him kneeling like a penitent statue. He remained so even as the hand came away to join its sister in fishing something out from under her blouse’s collar. It was a crucifix. One that he recognized at a glance as something inherited rather than bought. The beads were worn to a gleam by generations of grasping hands, the Son polished with fingertips and reverent kisses.

She held it out to him.

“I cannot,” he heard himself say. “It is…” Idolatrous? Against his teachings? True and true. But more vital still, “It is too precious. I could not rob you of this.”

“If—,” she began, then bit her tongue. “When you return, you may return this too if you wish. But you must take it now.” She put the rosary around his neck. “For your mother’s sake.” Her hands stayed down on his shoulders an extra moment. Pressing the beads as if she might knead them through to his skin. Her eyes pressed with as much strength and trembling into his own while her lips worked weakly around each breath, as if she had no suitable words left. A moment later Jonathan watched her disappear down the hall and out of sight. He shut the door noiselessly before slipping the icon under his shirt. It carried its owner’s heat and its thaw settled against the gooseflesh on his heart. He pulled on his overcoat. Thinking.

St. George’s Day. Did I make a note of that or not?

He couldn’t say. But Saint George brought something else to mind. His attention went back to his luggage. All in order. He would rush to re-order it after digging up his far-less-fine pair of shoes. The kind he saved for parks and trails. In fact, the same pair he had worn the day he first laid eyes on Carfax. There was some minor hope in him that the Count might want to show him around the castle grounds. He’d never been through a real forest, let alone on mountainous terrain. If there was a walk in store, he supposed he’d have to find a new place for the shoes’ treasure. Jonathan took said treasure out from a slit in the right shoe’s interior.

Here was the sharpened sovereign from his friend in the asylum window. Saint George and the dragon had been cleaned since he first handled it and now it caught the afternoon light like a sliver of sun. He couldn’t say why he kept it on him, let alone in his shoe. The easiest thought was that it was for an emergency’s sake. Just in case he wound up the victim of a pickpocket. Alas, it would buy him nothing in this land so far from English streets. He thought of tucking it in with the rest of his currency or burying it back in the heel. Instead, he fished the journal out and wedged it into the flap at the back cover.

“Keep it safe, George.” His baggage was put in order, then put into his hands, and, within minutes, were set at either side of his feet as he waited on one of the benches outside the Golden Krone for the coach. He did his best not to notice that a crowd was converging opposite him. Some of last night’s companions were among the throng. They whispered to newcomers, apparently also waiting on the coach, who in turn whispered to those who came along merely to know why Jonathan was worth staring at. He slipped the journal from his breast and danced the pen along a new page.

4 May.—I found that my landlord had got a letter from the Count, directing him to secure the best place on the coach for me…

He carried on a few lines more, up until:

I am writing up this part of the diary whilst I am waiting for the coach, which is, of course, late; and the crucifix is still round my neck. Whether it is the old lady’s fear, or the many ghostly traditions of this place, or the crucifix itself, I do not know, but I am not feeling nearly as easy in my mind as usual.

His pen stilled. Hovering over the paper for one, two, three heartbeats before:

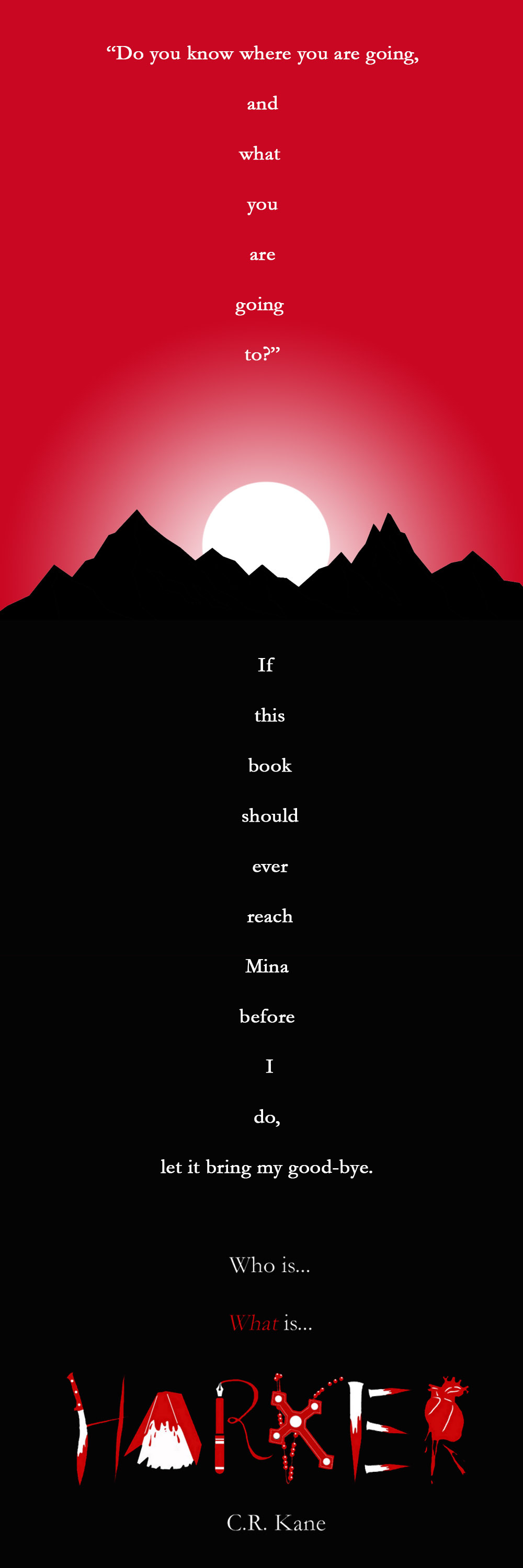

If this book should ever reach Mina before I do, let it bring my good-bye.

Here comes the coach!

He set the journal back in its place just as the horses came to a stop. The landlord got to the driver before Jonathan had even gathered up his things. Money was handed over, lips moved quick and quiet, and a long look was thrown his way by both men. They might have stared longer if the landlady had not called their attention, again in a language Jonathan couldn’t place. Whatever it was, it got the driver out of his seat and around the landlord. The latter of whom seemed to have aged and grieved through another decade as he stood there. Nor could he seem to meet the gazes of any of the others who were descending or climbing onto the coach. Upon seeing Jonathan rising with his bags, the old man’s face set back into a welcoming countenance.

“Young Herr! This way, please, up on this side.”

Jonathan was herded up into his place as the landlord tried to fill the air with friendly sound. He stopped halfway through what Jonathan could only imagine was a rote well-wishing for safe travel before the words lodged back in his throat. This close, Jonathan saw that the wrinkle-wreathed eyes were horribly bloodshot. He turned back to the Golden Krone and vanished inside before the struggling curl of his smile could fall entirely. He had to slip around the threshold where his wife and the driver were still talking. They were joined by a number of new faces. All in their turn paused to search the coach and find Jonathan’s face. Wonder and pity sat heavily in every glance.

More than their expressions matched. Certain words arose and drifted to him on the breeze in repetition. Jonathan took the polyglot dictionary from his bag.

Ordog: Satan. Pokol: hell. Stregoica: witch. Vrolok and Vlkoslak: referring to either were-wolf or vampire. Is Saint George tied up in so many ghastly things here? Walpurgisnacht should have had the lion’s share of horrors, I’d think.

The thought did not soften any of the sharp edges growing in his mind. Those edges honed to razors upon seeing how the swollen crowd’s hands all moved in unison. A sign of the Cross over their hearts, and then—

I know that sign. Knew it. Didn’t I? When I was small, I’m certain I saw them both use it.

Mr. and Mrs. Harker had made the gesture in earnest and in jest. A hand raised with index and little fingers jutting out. It was something to do with the nazar. Simple, so simple, he knew he was being foolish not to recall it. But the meaning slipped him just the same. Finally, he turned to one of his fellow-passengers. He was not one of the Golden Krone’s guests and seemed dumbfounded that Jonathan would ask after the sign’s meaning. Jonathan took the impression that his complexion being a shade deeper than the man’s own might be the cause for this. It wasn’t until it got across that he was an Englishman that the man’s expression changed to surprise, then worry, then a leaden sort of sorrow. A word was exchanged with the lady at the man’s side in a private tongue before he held up his own hand with the sign for Jonathan to see.

“Charm. Guard. Ward. Keeps away the evil eye.”

Memory turned swiftly over in him. Yes, yes, the evil eye. That hazy essence of ill will kept at bay by the shape of a hand or meeting the blue stare of the nazar. Jonathan looked again at the people before the Golden Krone. A sea of mingled gazes, brown and blue, grey and green, all settled on him like mourners’ stares regarding a hearse. They made a paradoxical tableau against the springtime brilliance of the oleander and orange trees. His musing broke at the sound of the whip being cracked. The coach pulled away.

The span of time between afternoon and evening was a strange one for Jonathan. It was at once the most enchanting and ominous stretch of hours he’d ever known.

If he had been charmed by the progress of wilderness and towns thus far, he was enthralled outright by the coach’s route through the Mittel Land. All the best of Nature at her grandest seemed to unfurl on either side of the road in great heaped slopes. Hills were furred all over with woods and forestland, sometimes with the odd curated spread of tended fields. Farmhouses peeled from the idyll poets’ verses bejeweled the closest edges of the horizon, guarded by their animals and sweetly blooming fruit trees. Apple, cherry, plum and pear sighed their perfumes after them. All this was cupped within the giant cradle of the Carpathians themselves. The late sun painted every towering slant and shadowed crag and crystalline waterfall with a richness that no painter’s palette or photographer could ever match.

Jonathan only embraced the glory of the view by the mercy of his companions’ choice to speak in languages which they knew he could not decipher. Even the dictionary was of little help. But though he couldn’t grasp the words, it was easy enough to tell their concern. Demons and the dead, were-wolves and vampires, witches and evil eyes.

The crucifix felt heavier whenever he dared to think on it. Thankfully, his attention was drawn away from the view and the murmurs passing around him by way of the coach’s speed. The driver grew merciless with the poor horses despite the state of the road. It was a rough course that only turned more trying for the animals’ pace. After a particularly harrowing lurch through a clump of mingled mud and old snow, one of the passengers dropped into halting German to explain that the road was pristine come summertime, but purposefully left rugged for spring.

“Why is that?” Jonathan asked.

“Because,” the lady nodded out at the flying horizon, “it is tradition not to keep them in too good order. The Hospadars, they would not repair them, lest the Turks suspect them of bringing foreign troops. Such times were always at the brink of war for one thing or another.” A greyish look passed through her face and others’. “Any excuse could be made to spill more blood.”

It was quiet in the coach for some while after that. At least until they rounded one impressive hill and came upon a unique snow-plush peak that loomed mighty as a titan’s throne. Jonathan’s closest neighbour took hold of his arm as he pointed at it.

“Look! Isten szek!—God’s seat!” The man crossed himself as he spoke.

It wasn’t long after this that dusk began to slip over the rim of the mountains and pool in the thinning space that held the road. In that shade there remained a handful of people making their way along the sides of the path. Some were on foot. Others rode by leiter-wagon. Almost all those Jonathan saw were en route to or already kneeling before some fantastic shrine put together amid whole gardens of upright crosses. Devotion bowed the heads of those before the shrines while those on the coach crossed themselves. Jonathan might have been moved by awe alone if it weren’t for the bandages.

There was a wealth of swaddling gauze peeking out of the roadside peoples’ coats and scarves. Goitre was Jonathan’s first thought.

Prevalent, but hopefully not severe. None of them look swollen.

Still, he felt his heart lurch on seeing a man walking with one hand on his great lance of a stave while his other supported a drowsy child against his side. She wore her own helping of thick gauze within her coat collar.

Once the coach passed them, evening seemed to fall like a curtain. Cold fell with it. The chill shadows poured in through the mountains and the bunching trees as if night itself were trying to shoulder past the wait for sundown. Every passenger grasped at themselves or each other as prayers began to leak from clenched jaws. The horses were assailed terribly by the driver’s whip as they fought the ever-steeper angles of the road. There would be a dozen welts on the creatures before they reached Borgo Pass.

“Sir,” Jonathan spoke up from his corner, “I can go by foot from here.”

Those who understood his German whirled around at him while the driver flinched in his seat. He looked as though someone had turned the whip on him.

This he covered with a poorly feigned cough before replying, “No, no, you must not walk here; the dogs are too fierce.” He turned from Jonathan to nod grimly at the rest of his passengers. A smile tried to carve its way through his beard. “And you may have enough of such matters before you go to sleep.” A few people offered their own thin smiles and nods in the man’s direction. None would look at Jonathan after. There was only one more pause when they came to a flat portion of the road. A heartbeat in which the driver leapt down and raced through the motions of lighting the coach’s lamps. Even with the sun still present through the serrated lines of the mountains—a hot red coal of light—the coach seemed at once to be the only visible thing left on Earth.

The impression only deepened as the last of the sunlight flaked away, turning the race toward Borgo Pass into something Jonathan could only liken to a miner plunging into the blindness of an unlit cave. Tree and rock and peak closed in high and close, every feature of the wilderness melting blackly together. Jonathan shivered from more than the cold. His companions took it worse.

While he couldn’t catch every word, their urgency and the swifter cracking of the whip added up to a joint plea for the driver to somehow make his abused horses outrun nightfall. Half a dozen tongues pleaded for the man to go faster, faster, please, God, faster! The darkness ahead cracked with a last filament of eerie grey light; sunset’s final offering. Jonathan was the only one who took note of it in silence. If the coach had been worried before, now its passengers descended into frenzy as the coach rocked upon the springs. Jonathan held to his seat with one arm and kept the man beside him from falling forward with his other. The mountains clenched like a fist as the road finally turned level.

This was the Borgo Pass.

The new flatness of the path sent the horses and their burden firing ahead into its gloom as if they meant to outpace a bullet. Something of this rush into full darkness rattled the air with a new energy. One that craned as many heads to observe the gathering pitch around the lamplit coach as they swerved to find Jonathan’s face. The man at his side suddenly took hold of Jonathan’s hand and pressed something in it.

“Keep it. In your clothes, under your pillow. So your rest stays well.” It was not a suggestion. The words were accompanied by a sign of the Cross and the gesture against the evil eye.

Jonathan looked down to find a familiar blossom. A full wild rose like the boutonniere the man in Munich had worn. The man stared at him with eyes like drills until Jonathan dutifully tucked the flower away.

“Thank you—,” was as far he got before another hand landed on his knee. As he turned to face forward, his hand was trapped again. This time a sachet was clapped into his palm by the woman across from him. It was fragrant. Spice, flowers, mint.

“God keep you,” she whispered. Her hand too made the Cross and warded off the evil eye. Jonathan was given no time for thanks or inquiry before the entire coach was busying itself with gift-giving that refused any refusal. With each token given, from the ancestral to the freshly-made, Jonathan was watched as he stashed every piece with his things. Blessings enough to make a church seem impious laced the air between them. So it went until the horses began to slow. A new wave of fear rippled through the group even as Borgo Pass’ opposite end showed a hint of its rough edges in the distance. If Jonathan squinted, he could see a distant scatter of lights that marked Bukovina.

Such distant embers were all but invisible as the sky seemed determined to erase even a flicker of surplus light. Moon and stars were swallowed by a sudden roiling of a thunderhead. The coach came to a stop at the border which seemed to halve the atmosphere between storm and stillness. Every spare eye searched the impenetrable void that now congealed under the clouds. Time crawled with crippled minutes as Jonathan searched with his fellows for a sign of anything in that featureless space. He waited for the glare of carriage lights, the sound of hooves from less haggard stallions than the quartet gladly catching their breath.

But there was nothing. Neither sight nor sound for four endless minutes. A fact that drew relief from the passengers with a mingled gust of sighs. For his part, Jonathan felt a war of distress and comfort crash in him. Comfort in that whatever peril his companions thought was sure to bound down the road had decided against it. He felt better still to have had the concern of so many strangers on his side at all. But with that acknowledged:

What now? Wild dogs or no, should I try to walk? Maybe the man is just running late.

As he pondered, Jonathan caught a murmur from the driver to the rest of the coach. His attention was on his open pocket watch and his words were in brisk hushed Hungarian.

Jonathan thought he heard him mutter, “An hour less than the time.” Snapping the watch shut, he turned fully to face Jonathan. His German, even rougher than Jonathan’s own, rattled out, “There is no carriage here.” Then, raising his voice to address the entire coach, “The Herr is not expected after all. He will now come on to Bukovina, and return to-morrow or the next day; better the next day.”

There was a hasty murmur of agreement as if from a herd of relieved chaperones. Jonathan felt at once like a child again, the adults all nodding high above his head, yes, yes, this was the right choice for him, of course. But the moment shattered as the coach itself jolted as if struck. It jumped in a shuddering half-sideways direction as the four horses tried to twist away from the barren road that led up into the dark. The driver cursed and fought with the reins as the animals brayed their panic.

That was when the screaming started.

First one voice, then another. Two and three and four more. Those who did not scream only stayed silent as terror clogged their throats. Hands flew frantically to cross their hearts and grasp at kin or spouses. Jonathan spied the reason for it all in the form of a calèche driving out of the blackness. Its sides and the stallions were so perfect a shade of coal that they seemed more to sculpt themselves out of the night than to pierce it. Jonathan braced with his fellows as the calèche fired up from behind, overtook, and pulled neatly parallel with the coach. The ruddy light of the lamps revealed the outline of a tall man sitting with the reins. His face was a buried mystery between a dark flowing beard and a broad black hat. The only suggestion that he had a face at all was the glimmer or his eyes. The lamplight painted them red.

Jonathan saw the hat tilt so that he addressed the coach’s trembling driver.

“You are early to-night, my friend.” The words were Hungarian and his voice was low, as if he barely drew breath.

The driver stammered back, “The English Herr was in a hurry.”

“That is why, I suppose, you wished him to go on to Bukovina. You cannot deceive me, my friend; I know too much, and my horses are swift.”

The talk revealed a flash of the stranger’s mouth. It was a sharp gash with sharper teeth. These stood out ivory-white against the bruised rose of the lips. Someone whispered:

“Denn die Todten reiten schnell.”

For the dead travel fast.

The calèche’s driver turned to the speaker with a grin. His teeth all but glowed under the lamps’ full light, seeming to stain them scarlet. The speaker paled and twisted quickly away, making both signs against evil as he did. But the driver had already turned from him to look directly at Jonathan. The twin points of his eyes seemed brighter.

“Give me the Herr’s luggage,” he said. Jonathan barely had a moment to brush his hands against his things before the driver was snatching them away and handing them over to the waiting stranger. Said stranger took everything with the ease of a man carrying pillows and neatly tucked them aboard the calèche. Jonathan followed after them, pretending not to feel something cold turn over in his stomach as the fingertips of his nearest companions brushed against his coat.

His feet had barely met the ground before the calèche’s driver took him by the arm. Jonathan had to bite his tongue against a gasp. The grip was tight nearly to the edge of pain. He wondered briefly if the man intended to secure him among the luggage rather than help him to the seat. But the grip disappeared easily enough once he entered the calèche, if with a less-than-needed clap of the heavy palm to his shoulder as though to be sure he wouldn’t try to rise. When Jonathan did not move, the stranger’s teeth flashed a last time—again, that scarlet gash—and then all at once he was at the reins again. With one snap, the svelte horses turned back to the climbing road and stole them away.

Jonathan looked over his shoulder and felt a leaden loneliness drop through him. That and surprise. Already the coach was a dwindling speck of rosy light in the dark. The tired horses’ breath still coiled away in white plumes. His former companions’ outline stood against it. Still crossing themselves. Then came the distant crack of the whip and the coach pulled away toward Bukovina. He kept his head turned until the last twinkle of the lamps disappeared. Thunder laughed to itself overhead and a fresh chill sank through his bones.

That’s it, then. Too late to turn back now.

He didn’t have it in himself to think the question, ‘Why would I wish to turn back?’ Not when his ears still rang with the shrill sounds of terror in the coach. Not when he had been loaded down with charms and prayers against evil by people who had known him only to fear for his safety. Not when his arm still bristled from where the driver’s glove had locked upon him with the implacability of a guard dragging his prisoner. Not when the crucifix sat like ice against his heart.

Said heart froze entirely when the calèche came to a sudden halt.

The driver murmured in German, “Apologies, apologies,” as he brought something with him from his own seat. Before Jonathan knew it was happening, a cloak was drawn over his shoulders and a weighty rug was tossed over his lap. Cloak and rug both were smoothed against him as though the stranger were trying to settle a dog’s hackles. “The night is chill, mein Herr, and my master the Count bade me take all care of you. There is a flask of slivovitz underneath the seat, if you should require it.”

“Thank you, sir,” Jonathan said with a nod. He had no desire to drink, grateful though he was for the opportunity. If ever there was a night when he wished for steadier nerves, this was it. Better still if some miracle might come along to wake him from the phantasmagoria that saturated each new heartbeat. As the driver steered straight on, then made a hard complete turn, then another straight shot, Jonathan began to wonder if he was not asleep already. Perhaps he was still in the Golden Krone and dreaming the entire journey. He would wake soon. Perhaps now, as he fought not to observe another queer turn in the night. That turn being:

He's taking us in circles.

He had ascertained as much two circuits ago when he managed to catch sight of a uniquely warped tree bough, gnarled as a reaching hand over the road. They passed it more than thrice. Even with only the dimmest glow coming from the calèche’s own lamps, there was no mistaking the path. Jonathan swallowed back the first and only unformed question he might have asked—

Sir, what are you doing?

—and let his hand slip under the cloak and up to his chest. His fingers walked over the lines of the crucifix and around the slim presence of the journal.

‘If this book should ever reach Mina before I do…’

“Stop. You must stop.” The words were silent. His only evidence of them was the white stream of his breath. He struck a match to read his watch by. Three minutes until midnight.

Are you here, Saint George? If not you, who? What?

Jonathan bit his tongue against mouthing the words themselves, but thought incessantly at himself to stop, for he must stop. Only there was no stopping. Just the calèche’s ceaseless rounding route. Over and over again as midnight encroached.

Somewhere far, a dog began to howl. It might have been singing from the comfort of some distant farmhouse. As it might be said for the next dog, and the one after that. All at once there appeared to be a choir of the animals all baying in a synchronized wail that might have covered the entire country’s worth of hounds. It was at once a pained and wild cry, as though every one of the creatures were joined in mourning the same fallen friend.

The performance was not to the horses’ liking and they reared anxiously as the volume increased. They trembled as they carried on, their breath trailing in broken streams. Yet it was not half so rankled a reaction as what came next. All at once the dogs were drowned out by a more cutting howl that set Jonathan shuddering as hard as the stallions. Here was the baying of innumerable wolves. Jonathan couldn’t say whether it was the echo or the nearness of the pack that lent the howling its volume, nor did he much care. There was an uncanny note in their sound that made his feet itch to run all the way to Bukovina.

They do not sound natural. That’s the trouble. The dogs took up their chorus one after the other and all bayed over each other. The wolves cry like a single voice.

He clutched at the seat to steady himself against the noise even as the horses fought against the driver’s hold. Finally the driver stilled the calèche entirely and, in what Jonahtan thought must be some trick of a professional tamer, hopped down to stroke and whisper the animals into a sedate state. They still shivered under his hands, but the wolves’ song no longer nettled them enough to think of fleeing.

That was why he was so comfortable setting you in place. He knew you would try to run too.

The thought broke off as the calèche plunged forward with new speed. Not back on the circling route, but onto a thin path that ran to the right. Jonathan thought for a moment that they must be going through a carved tunnel. It was only by the sparse lamplight that he could tell the route was tight-packed and sheltered with the closing in of trees and stone. The wind groaned through boughs and crags, carrying a cold gust that warred against the would-be storm. Thunder and its promise of rain were blasted away as if slapped by the frigid new breeze. What might have been a downpour turned instead to a sudden dusting of snow. A powdery blanket of the stuff rushed down to dapple the night.

Jonathan folded into himself as tight as he could against the wind. It sharpened almost to a shriek with its force, blowing away the last echoes of the dogs’ howling in favor of the wolves’. The horses brayed in fear or hate at as the latter grew nearer. All the while the driver turned his head left and right with an uncanny idleness. He looked as though he were on the lookout for a new restaurant rather than a hungry lupine army. Jonathan prayed the man’s sight was keener than his own. No matter how he searched, there was no spying anything beyond the range of the dim lamps.

Not until a point of blue appeared in the dark.

It was a single tongue of flame that flickered far off to their left. The driver spotted it just as Jonathan did and immediately halted the horses. With that he shot off into the dark, toward the burning blue speck. Jonathan felt his mouth fall open on a question he could not quite think of. What could he ask?

‘Sir, while I admit it’s an intriguing sight, are you sure you want to leap out into the wolf-infested forest in the dark? Sir?’

The driver returned before the thought had finished. He returned to his seat and drove on without a breath of explanation. Soon another blue flame was spotted. The process repeated. Again. Again. Again. On one stop he was close enough that Jonathan saw him piling a hill of stones together where the sapphire light danced, as though making a cairn. At another stop, the light seemed to banish the laws of waking reality entirely and showed through the driver as the man crouched between it and the calèche. The sight calmed as much as disturbed Jonathan for the obvious reason.

Clearly he had fallen asleep.

He must have. Either on the calèche or in his room at the Golden Krone, or even the Hotel Royale. He might be all the way back in Exeter. Not waiting to wake for the train, but for another day under Mr. Hawkins’ office roof, far and warm against another spring shower, he must have kicked off the covers in his sleep, no wonder he was so cold, and oh, yes, his brain had turned to gruel with stress over the examination around the corner, Mina and Hawkins both had warned him against overwork, and now look where that left his dreaming mind, it served him right—

Another twinkle of blue hovered far, far off. Less than a pepper grain’s worth of light. But it was there and the driver halted the horses once more to take after it. Jonathan watched him seep into the blackness of the forest like a drop of ink returning to its bottle. And waited. As the wind lowed. As the wolves quieted. As the horses first fidgeted, then snorted, and then, as the people of the coach had before, screamed. Jonathan had never heard such a noise come from any animal, let alone a horse. It was a nigh deafening din riddled with a horror so deep and comprehending of a threat that Jonathan might have taken it for the sound of them dying where they stood. It was then that the moon finally found a window in the breaking clouds and threw its tarnished light down through the branches.

He saw the eyes first. They threw back the moonlight like a hundred chips of mirror glass. Next were the teeth, all gleaming teeth and lolling tongues. Last, he saw the bristling shapes of the wolves themselves. A legion that circled the calèche from every angle. Their army stared in silence for one final moment, as if they had been waiting for the moon to reveal them. Jonathan could not scour the thought from his head—that horrid certainty that the creatures wanted to be seen first.

What animal wants an audience with its prey?

There was neither chance or desire to dig for an answer. Not when the wolves took that moment to shatter the quiet with a renewed howl. This one was not a single mingling note. No longer a choir, but a garbled and hating cry that fractured into snarls. The horses reared and thrashed in place as the wolves snapped their jaws just out of reach of their hooves. It was a powerful sound, that snapping. Like massive stones crashing together. The kind that could break bones like a man broke bread. And if so many of the creatures were here, closing in—

The driver. They would have to have passed the driver to get here. Oh, God.

Jonathan stood from his seat and found he no longer felt the cold even as cloak and rug fell from him. He cupped his gloves around his mouth to shout.

“Sir! Can you hear me?”

No answer from the dark. Had something moved out there? A snapped twig, a rustle of leaves? He couldn’t tell. His only real answer came from the wolves who bayed back at him. Some even reared as the horses did, as though thinking of leaping aboard. His palm itched for lack of a hardwood handle.

Should have brought it along. What else is there? A shaving razor? A heavy book?

Jonathan clambered up to the front. He did, in fact, have a book on hand that he might dare to sacrifice—a weathered hardcover of Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo. With an apology to Edmond Dantès, Jonathan dangled his left arm out in the open to hammer against the side of the calèche with the novel. It made an impressive noise. At least enough to make the nearest wolves flinch.

“Sir!” his clipped German rang out again. “Sir, if you can hear me, we need to go! The wolves have cut off the road!”

Still no answer from the driver. Fear ran laps in Jonathan’s chest as he dared to consider the worst.

The man was dead.

The man was dying.

The man was hurt.

The man needed help.

There would be no forcing the calèche through the trees. One of the horses could make it, but the stallions would still be trapped by fear of the wolves’ jaws or else run madly without any reins upon them. He was thinking of fashioning a torch using the rug and his matches when a voice broke out of the murk. It intoned a single word. One he did not know even as he felt the weight of its command in his mind.

Stop.

Jonathan looked up just as the wolves did to face the road.

There stood the silhouette of the driver. Even with the frailty of the lamps, his eyes shined that inexplicable red. Jonathan watched as if in a trance as the man’s long arms rose and swept out as if parting a curtain. Again, that unknown tongue and its phantom press of meaning.

Begone.

As if he had ordered the sky itself, another cloud passed over the moon and erased the world down to the calèche and its quivering horses. The cloud skidded away. With the moon’s return, Jonathan saw that every wolf had disappeared. This, without a sound. Not a howl, a huff, a parting snap at the horses. They were just gone.

Asleep. Jonathan had to be asleep.

“Mein Herr.” He started at seeing the driver abruptly at his side, about to climb back in his seat. The crimson points of the man’s eyes burned in the hat’s shade. The teeth, so like the wolves’, flashed through his beard. “Did you wish to ride up front?” The voice, still so low, sounded at once like an invitation and a threat. Jonathan scrambled back to his place. His tongue felt weighted against offering any word, be it of inquiry or apology. The driver’s head turned to follow him. He did not climb in until he saw that Jonathan covered himself in the cloak and rug again. The reins were shaken. Off went the horses just as another curtain of clouds pulled over the moon.

Jonathan cradled himself under his borrowed covers while they pressed onward, upward, further and further from the concept of other people and the sane lines of civilization. He shut his eyes as if the dream, if it was a dream, demanded they be closed so he could open them and behold a waiting hotel room or his own apartment. But there was no shutting out the chill or the trundling of the calèche around him. He kept his eyes shut regardless. It felt infantile, but it was the only hiding place left from the assault on rationality that the voyage had become.

I am hiding, aren’t I? From blue fires and wolves that come and go like a vicious magic act. Or else they are the ghosts of wolves been and gone. Saint George, are you up here? Or have you gone riding to save poor Lenore from Death’s cruel trick of a marriage bed? I wonder if there are cemeteries this high up in the mountains. However high we’ve gone. We will come to a stop only to see that Castle Dracula is a mountain itself and it takes its name from the dragon living inside, his mouth open and waiting for the driver to plunge us in, men and horses and all and then, then I might wake up.

He might have laughed to himself but for his worry that the hysterical hiccough might draw attention. Jonathan wished more than anything in that moment that he might condense and silence himself so thoroughly that he would disappear from the calèche completely. Instead, he cracked his eyes open. Relief and concern crashed against each other as he did. Here was moonlight again, finally free from the last tatters of the clouds. It fell in a pale yellow upon forested ground that was gradually losing its crushing hold upon the road. Being able to make out details at all in the impenetrable night was a welcome thing. Mostly.

For now he saw that the driver was pulling up to the courtyard of what must be Castle Dracula. The vision worried as much as heartened for he felt he should have noticed the titanic place’s approach long before closing his eyes, even at a distance. Indeed, the structure truly was something of a mountain in itself, if one assailed by centuries of abuse. Broken battlements and rooftops rose up in broken angles as if to claw at the stars. These and a number of sprawling archways were all he could make out with the moon’s ample sketching, showing the shape of Castle Dracula only as a canny artist might imply the stature of a monster lurking in a painted abyss.

But what worried Jonathan most was that Castle Dracula had no lights of its own burning. The only glow in the place’s towering windows was the reflection of the moon itself.

Am I really expected here? Are any of the Count’s people awake?

And, because his mind was in the mood to self-sabotage:

It looks like a crypt.

Jonathan might have pinched himself right then had the calèche not come to a rapid stop in the courtyard. The driver was at his side again in nearly the same instant, his gloved hand extended to catch Jonathan’s. Once more there was that steely strength that held back just short of crushing. Jonathan had often been on the receiving end of similar clasps from peers and clients who had done their utmost to make his bones grind together under the pretense of not knowing their own strength. He had long since made it a rule to not only not return—or, in many cases, outdo—the pressure, but not to show any awareness of the other man’s effort.

This was a harder task tonight. Not merely for the obvious restraint of the driver’s hold, but for the fact that he did not release Jonathan’s hand until he’d pulled Jonathan up to the very doorstep like a parent dragging a surly toddler into place. The image was not helped even when Jonathan’s hand was freed as the driver again planted his palm against Jonathan’s shoulder in a smoothing gesture—

Stay, mein Herr. Stay.

—before fetching the luggage and setting everything at Jonathan’s feet. The man did not pause, but shot back to his seat in the calèche and drove the horses out of sight. The sound of hooves dimmed away. Silence rushed in.

Jonathan regarded the colossal doorway he now sheltered in. Stones that were nearly boulders formed the arch of it and housed the great slabs of the twin doors. These he imagined might be as thick as the very trees they were carved from. The few gaps there were in the wood showed only more darkness on the other side. A darkness that seemed to watch him in turn. He turned his face up to the moon.

The latter only had half its face turned to him, paying attention in a way that he could not tell between bored or baleful.

To keep reading, go here:

Another banger!! 👏👏👏 And here we are, at the mouth if the lion's den...